Yves here. This post usefully estimates how deep and durable the costs of war really are. The subtext is that they are more severe than commonly assumed.

By Efraim Benmelech, Harold L. Stuart Professor of Finance and Director, Guthrie Center for Real Estate Research, Kellogg School of Management by Northwestern University Northwestern University and Joao Monteiro, Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF). Originally published at VoxEU

Wars leave deep and lasting scars on economies. Using data for 115 conflicts across 145 countries over the past 75 years, this column documents large and persistent declines in output, investment, and trade following the onset of war, with no evidence of recovery even a decade later. Government revenues collapse while spending remains stable, forcing reliance on inflationary finance and short-term debt. The findings show that the true cost of war extends far beyond the battlefield, reshaping fiscal and monetary stability for years to come.

The world is once again mobilising for war. Military budgets have surged to levels unseen since the Cold War, driven by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, renewed Middle East and East Asian tensions, and a widespread belief that peace can no longer be taken for granted. Governments are scrambling to raise defence spending while facing already-strained public finances, stubborn inflation, and rising interest rates. The fiscal and macroeconomic consequences of this new age of rearmament are likely to be profound – yet research offers surprisingly little systematic evidence on how wars affect economies.

Some recent contributions have started to fill the gap. For example, a VoxEU column by Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Vittal Vasudevan estimates that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may cost around US$2.4 trillion and inflict permanent output losses of at least fifteen percent in the belligerent countries (Gorodnichenko and Vasudevan 2025). Another (Federle et al. 2024a) shows that major conflicts reduce GDP by over 30% within five years and generate lasting inflationary pressures (VoxEU, 2024). A related piece (Harrison 2023) details how governments financed total wars through debt, inflation, and coercive state action. These columns build on a broader academic literature documenting the heavy economic toll of conflict – from Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003) on the Basque Country, Collier (1999) on civil wars, and Cerra and Saxena (2008) on deep and persistent growth losses, to Blattman and Miguel (2010) on war’s long-run scars, Barro (1987) and Harrison (1998) on war finance, Hall and Sargent (2014, 2022) on fiscal-monetary consequences, and Federle et al. (2024b) on the international spillovers of conflict.

A New Global Dataset on the Economics of War

In our recent research (Benmelech and Monteiro 2025), we provide the first large-scale, cross-country evidence on the macroeconomic consequences of war for the belligerents. We construct a dataset covering 115 conflicts and 145 countries over the past 75 years, including both interstate wars (state versus state) and intrastate wars (state versus non-state).

We use a stacked event-study design: for each conflict we compare belligerent countries (that are not simultaneously involved in other conflicts) to never-treated control countries, include conflict-country fixed effects to absorb time-invariant determinants and conflict-region-year fixed effects to capture regional time trends.

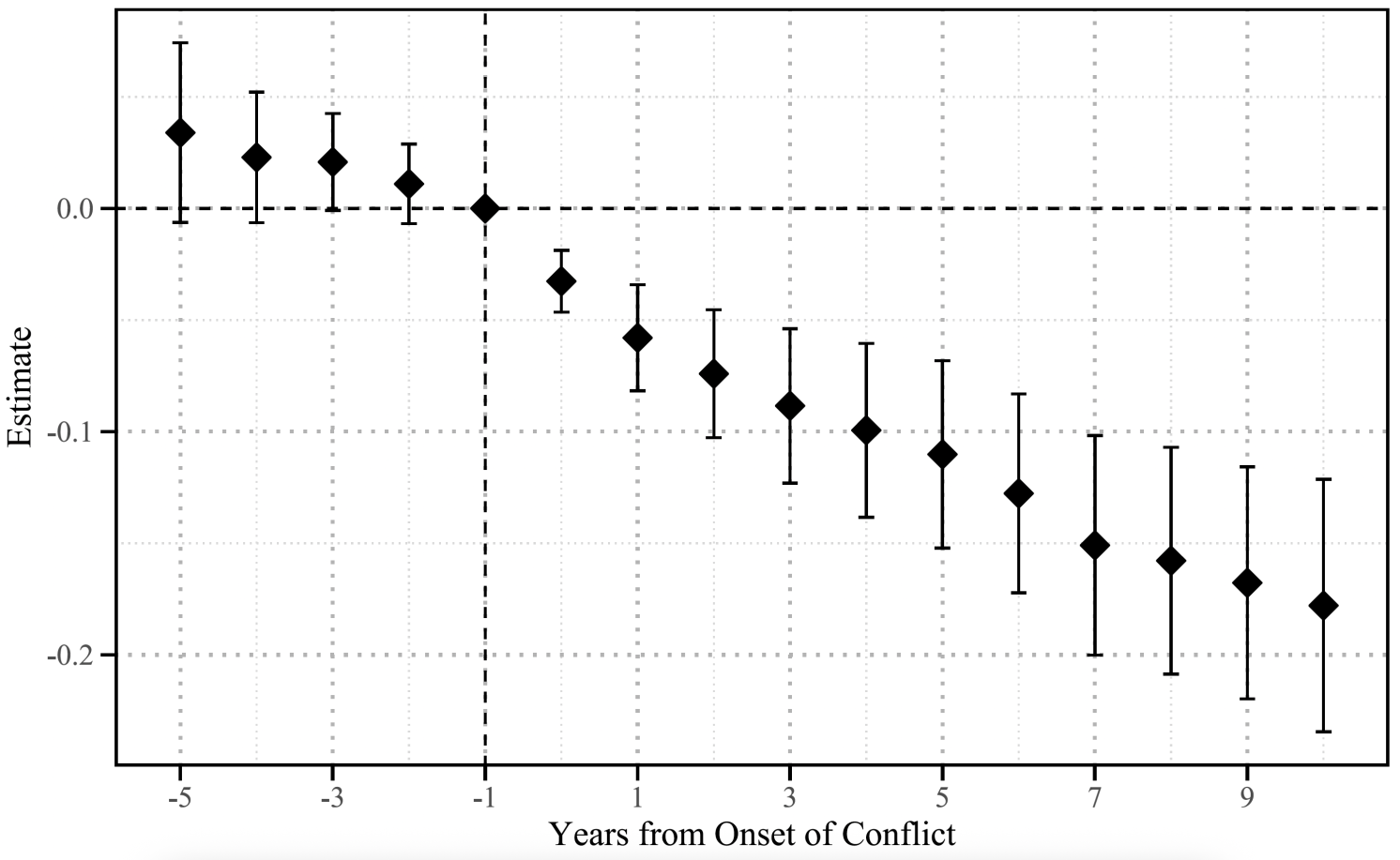

GDP Collapses – and Does Not Recover

On average, we find that real GDP falls by about 12% (on average) over ten years for treated countries relative to control countries, corresponding to an absolute loss of more than $28 billion (in 2015 prices). At the onset of conflict, the drop is modest (≈3.3%), but then the contraction deepens to about 16% after ten years. Consumption and investment fall sharply; exports fall by 12% and imports by 7%; and the current account deteriorates by around US $2.1 billion.

Figure 1 Effect of conflict on GDP

Conflict is associated with a destruction of capital stock. Consequently, one might expect investment to bounce back due to the higher marginal productivity of capital. Instead, we observe a collapse: real investment falls by around 13%, and real domestic credit drops by 20% – larger than the output loss. Lending rates do not fall, ruling out weak demand and pointing instead to tightening credit supply.

We interpret this as evidence that war erodes collateral values and constrains borrowing, particularly in lower-income economies with shallow financial markets. We also find that the adverse effects are much stronger for low-income countries: investment falls more, trade disruptions are larger, and the import-intensive nature of capital goods in such economies magnifies the shock.

Fiscal Collapse and the Short-Term Debt Trap

War also puts enormous strain on public finances. We document that real government revenues fall by about 14%, while real government debt declines by around 9%, despite nominal debt rising in local-currency terms. Meanwhile, government expenditures remain roughly stable – so the debt-to-GDP ratio stays constant – but the underlying real dynamics reveal fiscal fragility.

We also show that the share of long-term debt falls by about 2.2 percentage points (≈1.2% of GDP) as governments shift toward short-term debt to deal with risk and constrained access. This shift is economically significant – governments shift 1.2% of GDP from long-term to short-term debt – and is associated with a higher rollover risk, which makes these already depressed economies more vulnerable to financial crises.

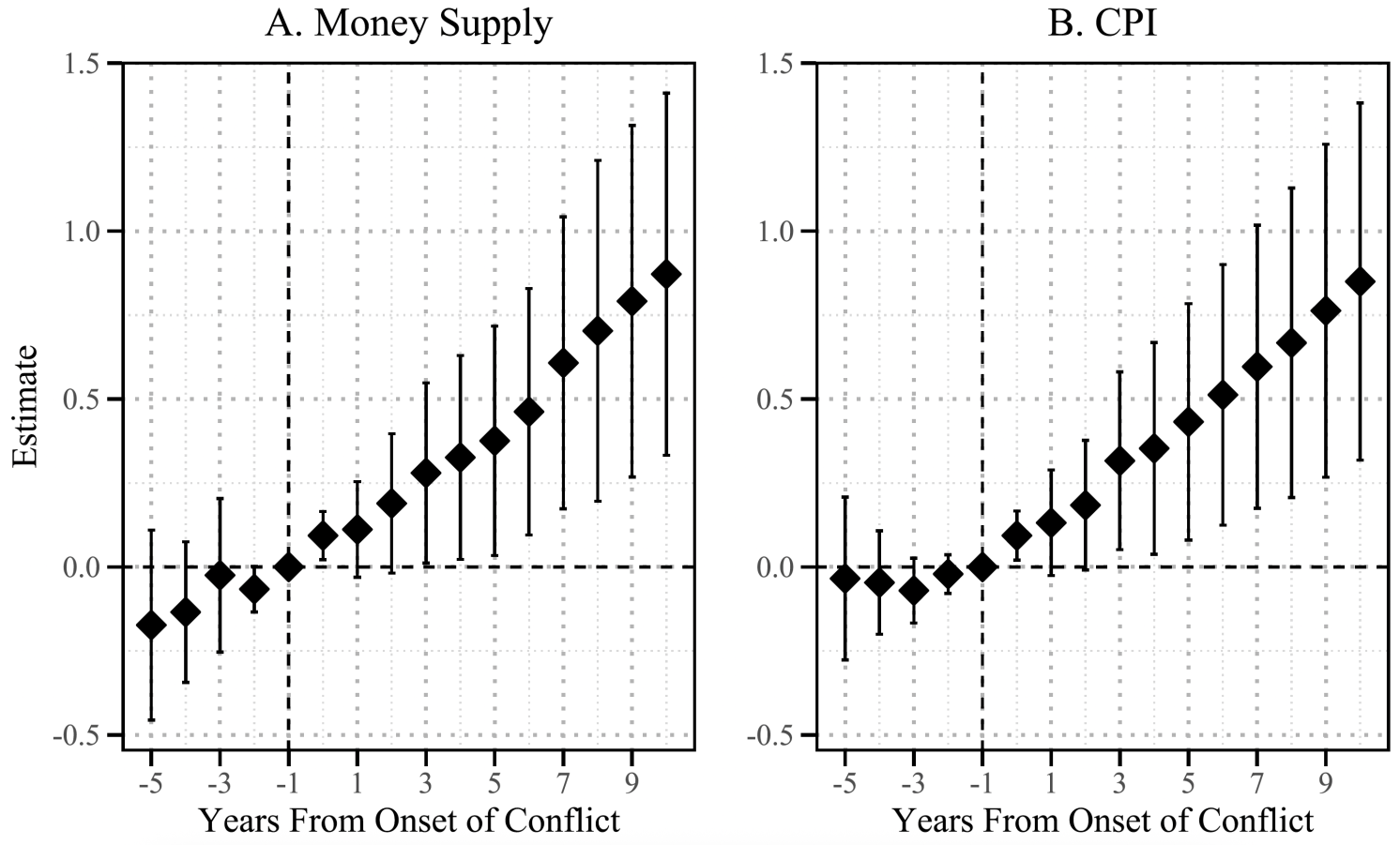

Inflation: The Silent Tax of War Finance

In the decade following the onset of conflict, we observe that the consumer price level rises by about 62%. In comparison, the nominal money supply increases by about 67%, yet real money balances remain unchanged. This pattern is consistent with inflationary financing of government deficits rather than real cash hoarding. War thus triggers a regime of fiscal dominance: deficits, monetisation, and inflation feed into each other.

Figure 2 Effect of conflict on CPI and money supply

Policy Lessons: The True Cost of War

Policy Lessons: The True Cost of War

The main takeaway is this: the costs of war are not temporary disruptions; they are large, persistent, and multi-dimensional. Wars do not simply destroy capital and infrastructure; they undermine the very financial and monetary foundations on which modern economies rest.

For policymakers facing rising geopolitical risk and a return to major military mobilisation, two points stand out:

Maintaining credible fiscal and monetary frameworks matters even – or especially – in wartime, because the legacy of war depends on how it is financed.

Reconstruction is not automatic: without access to credit, stable institutions, and affordable capital goods, economies may remain in the slump for a decade or more.

In short, war may end with treaties, but its economic scars endure long after. Recognising the persistence of these scars should shape both how we wage and how we recover from conflict.

See original post for references