Most retirement savers insist they want to be in the driver’s seat when it comes to investing their money. But new research suggests they may actually prefer a chauffeur.

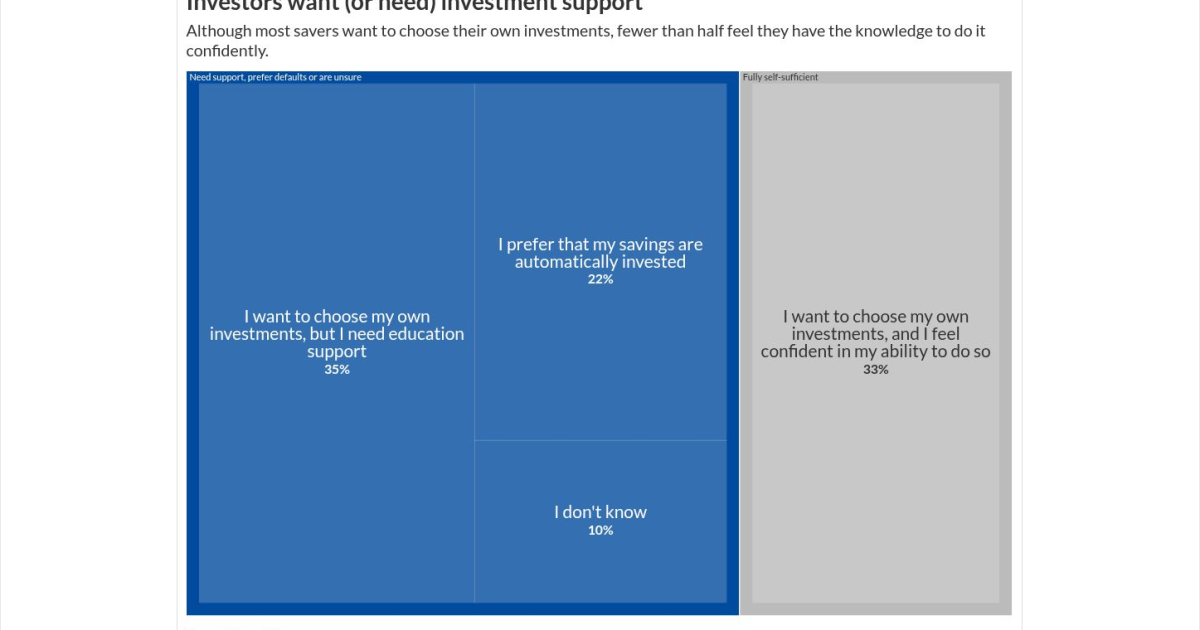

According to the 2025 Global Retirement Savers Study by T. Rowe Price, 68% of savers say they want to choose their own investments. Yet the data reveals a gap between aspiration and reality: 67% of savers use default investment options or professional management, often admitting they need educational support or simply don’t know what to do.

Just one-third of savers both want to make their own investment choices and feel equipped to do so. Another third want control but say they need more guidance. The rest lean toward defaults: 22% prefer automatic investing, and 10% aren’t sure what approach they want.

The survey, which included 7,000 responses from retirement savers across the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan and the U.K., found that American savers rank workplace plan providers and financial advisors as their top sources of information for financial advice, above the global average.

Still, even with strong reliance on expert information, advisors report that plenty of clients want to steer their investments themselves. Advisors say that’s not inherently an issue, but it does require a thoughtful approach.

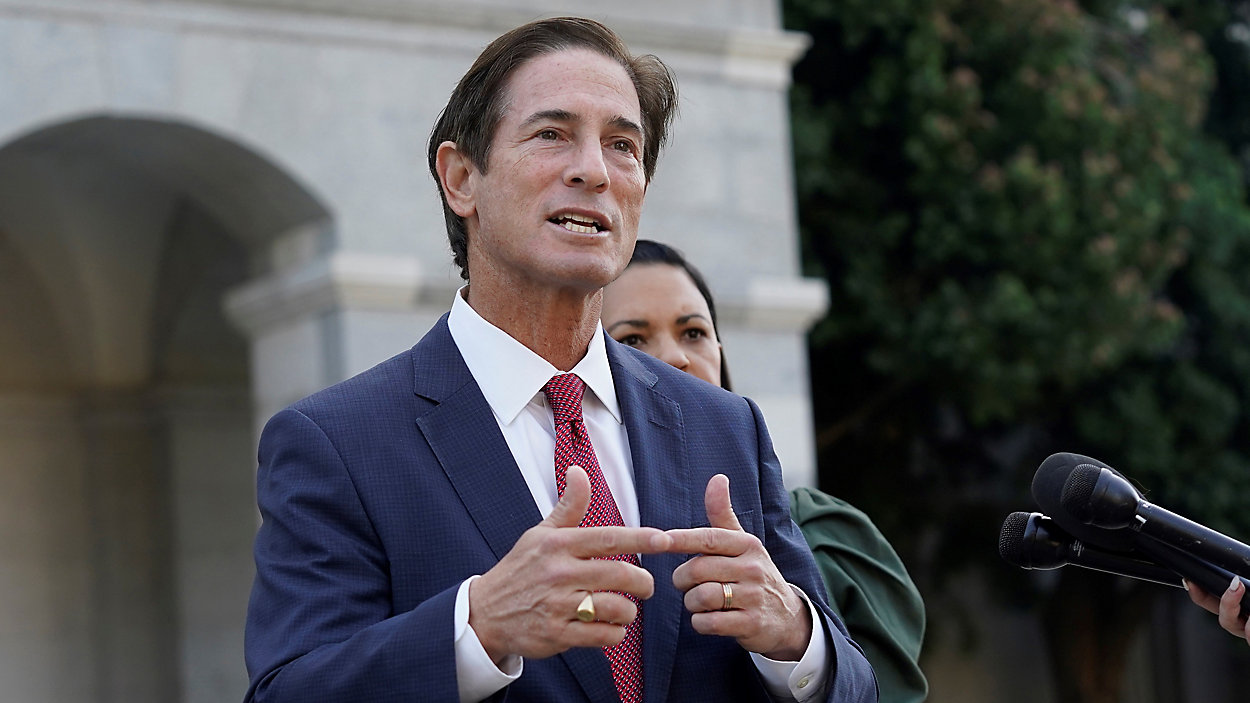

At San Francisco-based Wealth Script Advisors, founder Alex Caswell said they offer two investing options to accommodate different client preferences.

“We can either offer a fully self-managed investment approach with guidance, or we can take discretionary ownership for a part or all of the clients’ investments,” Caswell said. “I find clients usually fall into both buckets.”

“There is a level of wealth they want professionally managed, and some that they want some advice on,” he added. “It usually comes down to having trust and confidence in delegating the investment decisions to a professional they have never worked with before.”

Digging deeper into what clients really want

Trust isn’t the only barrier advisors encounter when working with clients who want to manage their own investments.

According to Joy Slabaugh, a financial therapist and the founder of Wealth Alignment Institute in Longmeadow, Massachusetts, clients often feel a self-imposed pressure to manage their own investments, even if they don’t really want to.

“I’ve noticed many, many people who seem to have a big ‘should’ about managing their investments,” Slabaugh said. “They believe they should want this even when they don’t. What’s more, they think all sorts of negative things about themselves are true if they don’t want to manage their investments. And so, they tell themselves they do want this.”

But according to Slabaugh, when advisors ask deeper questions, it becomes clear that most people want minimal involvement in managing their investments.

She often poses a variation of a simple prompt: “If you had a magic wand to design your ideal life, how involved would you want to be in managing your investments?” The answer quickly helps her uncover the clients who really want to manage their investments versus those who simply feel like they should.

In practice, advisors say it’s rarely an all-or-nothing choice. Getting clients comfortable with letting go of investment control usually happens gradually.

“At the end of the day, getting them from point A to point B may require several iterations of advice and management,” Caswell said. “However, even taking the initial step of improving their asset allocation or flagging bad investment choices is a big improvement and a move in the right direction.”

When clients can, and should, manage their investments

Compared to the average client, financial advisors are generally better equipped to make investment decisions than their clients. But that doesn’t always mean they should.

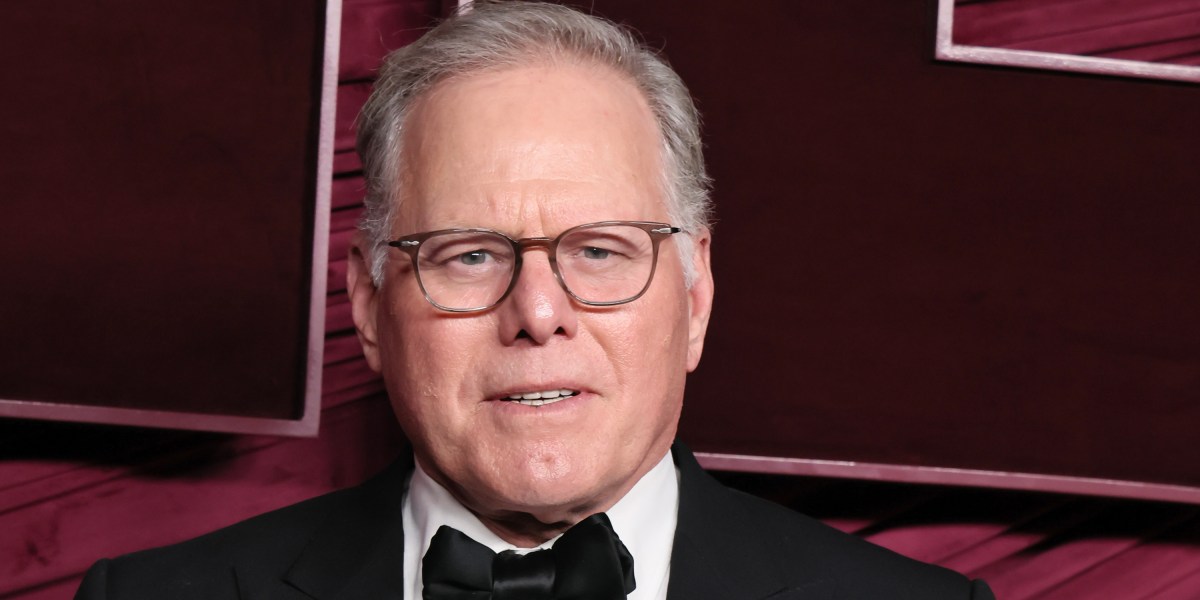

Buddy Thomas, the founder of San Diego-based Superior Planning, said that across four decades of work as an advisor, he’s found clients to be “very capable of making the decisions that are in their best interest (even better than what I might recommend) as long as they understand the implications of their choices.”

“A primary barrier is the overwhelming amount of unnecessary, confusing industry jargon we advisors use,” Thomas said. “Just as a good surgeon can explain a patient’s situation in simple terms for them to make life and death decisions, so can we.”

Advisors should also be capable of providing the necessary information to a client and executing on their decision, even if they disagree with it, Caswell said.

“If a client wants to make an investment in something we wouldn’t recommend ourselves, our job is to give them the pros and cons of their decision and our opinion,” Caswell said. “However at the end of the day, it is the client’s money and their responsibility to make and live with their decision.”