The Financial Times has a new piece on a growing social problem in many countries: the fate of young adults who fail to land jobs after college or high school. While it’s hard to get good data on this cohort, there is plenty of evidence of high levels of youth unemployment, not just in Western economies, but China as well, pointing to the risk that these individuals become socially isolated and never become integrated into “normal” life.

This is yet more evidence of the pattern set forth in Karl Polyani’s classic The Great Transformation. Polyani described how the operation of capitalism was destructive to society, and that that process was blunted but not halted or reversed by reforms and regulation.

Here, what we see is both business leaders and governments abandoning their duty to provide for sufficient work in a system where for the considerable majority, selling one’s labor is a condition of survival. Corporations been somewhat stealthily and in recent years, openly hostile to increasing their workforces, more and more depicting headcount shrinkage as a badge of honor. These cuts have been falling hard on entry level workers. We have been pointing since the inception of this site to periodic cries for help on the tech site Slashdot, of fresh computer science grads failing to land jobs and seeking advice. The greybeards confirm that this is a serious issue yet can seldom give guidance as to what to do. Starting in the early 2010s, there were more reports of technology decimating entry level jobs in the law, where scut-level research and drafting were critical to yeomen learning their trade.

We see these practices as destructive even on the level of individual companies. Managers have come to treat their workers as disposable and seem to relish the power that greater employee precarity give them. But disposable workers will not be loyal. In addition, turnover comes at the cost of screening for replacements and training them (they at least have to learn certain procedures and rules). But the boss class might not mind that because that extra effort falls on them, falsely increasing their claims to value.

But even if one can contend that these new norms are good for individual enterprises, they are clearly damaging on a larger societal level. Having more and more young adults become dependents, either of their families or of the state, impedes household formation and child-bearing. Demographic growth is one of the two drivers, with productivity growth, of economic expansion. It is true that slowing/reversing population growth is necessary to have any hope of ending resource depletion, environmental degradation, and species loss. But the manner in which this is happening is to enrich the top wealthy, who are not cutting back on their profligate, destructive lifestyles, offsetting potential planetary benefits.

One of the odd features of this modern immiseration of the young is that the soma of devices may be serving the elites by shunting energy and attention into isolation, when in decades past, at least some of the disaffected young might have taken to the streets or otherwise joined organizations not part of respectable society (including gangs). But a cynic might point out that smartphone addiction not only leads to disengagement but often depression, and medicating the young is another way to milk them without having them become perceived liabilities in the form of pesky workers.

Before turning to the Financial Times story, some snippets confirming the extent of the underlying driver of high levels of youth unemployment. The last official US jobs data in the US, for August 2025, showed that college graduates aged 20 to 24 had an unemployment rate of 9.3%, markedly higher than that of older degree holders (25 to 34 years olds came in at 3.6% jobless). The pattern of high levels of unemployment for new grads has been in play since the pandemic.

Even with a lot of the young sitting on their hands, many employers are instead bringing in foreign labor:

Around one dozen Vermont ski resorts are hiring close to 1,400 J-1 visa workers from overseas this winter.

America’s a big country with soaring youth unemployment.

Why not recruit at home? pic.twitter.com/f4FiCBxRwZ

— Barefoot Student (@BarefootStudent) November 12, 2025

And it’s not just the US:

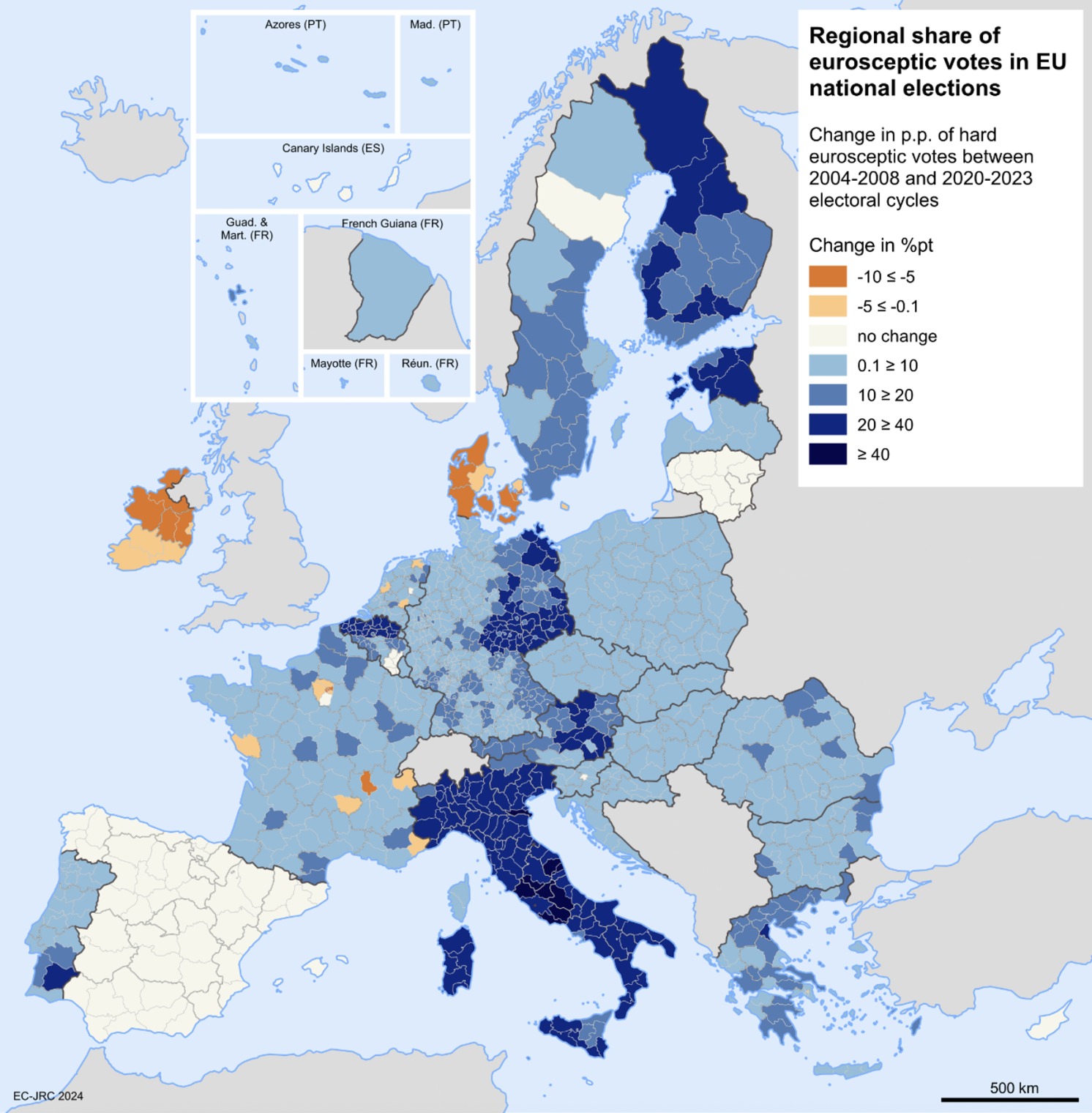

EU #youth #unemployment in September 2025:

🇪🇸25.0%🇸🇪24.0%🇷🇴23.5%🇫🇮21.5%🇱🇺20.9%🇪🇪20.6%🇮🇹20.6%🇬🇷18.5%🇫🇷18.3%🇵🇹18.1%🇱🇻17.6%🇨🇾17.2%🇭🇷16.7%🇸🇰16.2%🇱🇹15.2%🇪🇺14.8%🇧🇬14.5%🇭🇺14.4%🇩🇰13.9%🇧🇪13.8%🇵🇱13.0%🇮🇪12.2%🇸🇮12.2%🇦🇹11.9%🇨🇿10.2%🇲🇹10.1%🇳🇱8.8%🇩🇪6.7%@EU_Eurostat

— EU Social 🇪🇺 (@EU_Social) November 5, 2025

Canada’s Youth Unemployment Rate significantly understates the Youth employment crisis. This is because the Youth are leaving the workforce.

Now, after importing millions to compete with them for jobs, the Boomer Party of Canada is asking them to hold the bag. Shameful. pic.twitter.com/c3dS7xkweX

— Richard Dias (@RichardDias_CFA) November 5, 2025

Reading the IMF Asia Outlook and youth unemployment is up across the board, especially in South Asia and China. pic.twitter.com/MLP2aQk7kk

— Trinh (@Trinhnomics) October 31, 2025

After China’s youth unemployment rate came in at over 20% in 2023, the government retired its method of calculation and issued a new series in December 2023. Even so, this “new better” approach reported youth unemployment at 18.9% in August, which did improve to a mere 17.7% in September.

Countries that show lower levels of unemployment in the young may be suffering from exits:

Italians still keep moving away from Italy. That’s one reason why youth unemployment improved over the last decade (there are just no young Italians left to be unemployed). Germany remains the top destination. HT @maps_interlude pic.twitter.com/6JUirEX9hv

— Simon Kuestenmacher (@simongerman600) November 1, 2025

Now to the Financial Times account. Even though this is a UK-centric piece, many of its observations hold true for other nations. It starts with efforts, starting in the UK in the 1990s, to identify NEETs, as in young people Not in Education, Employment or Training. The wee problem is that this cohort would also include stay-at-home moms and so naive data collection would be misleading. Even so:

The concept rightly went on to become a staple of international economic statistics, with research consistently finding that NEETs are at risk of life-long socio-economic scarring, remaining at significantly elevated risk for worklessness and health problems for decades….

The figures are concerning enough, but there are additional factors beneath the surface which mean both that these groups are struggling more than in the past and that reversing the trends might be growing more difficult.

One factor is the deterioration in housing affordability seen in many countries, leading to a growing share of young adults never leaving the parental home, which can diminish the incentives to work.

Another big challenge is the role played by anxiety and other mental health conditions.

In the UK, a large and growing share of socio-economically isolated young adults report suffering from a mental health problem that prevents them from working or seeking work. This, combined with the nuances of Britain’s welfare system, may be one reason the UK’s long-term youth worklessness trend is so steep. Changes in the relative rates of unemployment and disability benefits have led many people to transition over from the former to the latter, and once on health-related benefits many fear they will lose them if they seek to re-enter the workforce.

An additional UK-specific concern is that steep increases to the youth minimum wage and policy changes that increase the cost to businesses hiring low-wage workers are hitting employment rates for young people.

A third point highlighted to me by Louise Murphy, senior economist at the UK’s Resolution Foundation think-tank and a specialist in young adult worklessness, is that this group has been acutely afflicted by the rise in time spent alone as smartphones and other digital technologies have displaced in-person socialising. In the US, young people who are not in work, studying or raising children now spend seven hours per day completely alone, up from five a decade ago.

In the US, where we have stunningly high medical care/insurance costs adding to housing costs as a barrier to independent living, there a cliff effect with Medicaid. Even states with expanded Medicaid typically have a cutoff of 138% of the Federal poverty line. And consider states like Alabama, with a cutoff for singles at a mere $1,014 a month,, or Arkansas at $1,044, or Colorado and Georgia, both at $994. But those are generous compared to Kentucky at $235 and Maryland at $350.

So the relentless march of neoliberalism is now doing serious harm to the young, who have historically been the promise of the future. And fevered tech overlord dreams of further cutting employment levels among the educated have only just started getting going (many argue that the round of big company job cuts under the market-pleasing justification of AI were to a fair degree to unwind over-hiring during Covid). But neoliberalism, enabled by smartphones, has succeeded well beyond Thatcherite dreams of creating atomization and wrecking the sort of social cohesion that in earlier generations might have engendered pushback or mutual help associations, not just from stuck-at-home grads but also the parents still supporting them.

In other words, to quote a curmudgeonly friend, “If you want a happy ending, watch a Disney movie.” Aside from slowing and reversing population growth in high-resource-consuming societies, it’s hard to find one here.