How to know when to accept clients and when to terminate the relationship.

Highlights

Audit firms must follow PCAOB guidelines, particularly the upcoming QC 1000 standard, which mandates a formal, risk-based quality control system for client acceptance and continuance.

Effective due diligence involves evaluating management integrity and financial health, ensuring firm independence under stricter AICPA ethics interpretations, and communicating with predecessor auditors to identify red flags.

Firms must internally assess their capacity and competence, ensuring adequate industry expertise and partner bandwidth for quality supervision.

An audit firm’s decision to accept and continue a client carries significant weight — and for good reason.

Accepting engagements beyond a firm’s professional competence violates Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) standards and increases risk and reputational harm. That’s why having risk-based audit client acceptance procedures in place is essential.

To help firms navigate the nuances, this article peels back the layers to address how firms can identify risks when accepting new clients, when it’s time to end a client relationship, how firms can better manage audit client engagements with ease, and more.

Jump to ↓

What are the PCAOB guidelines for audit client acceptance procedures?

Identifying risks when accepting new clients

Due diligence red flags for auditors

How audit leaders can handle client capacity

Client continuance and knowing when to end the relationship

How to manage audit client engagements with ease

What are the PCAOB guidelines for audit client acceptance procedures?

The PCAOB establishes requirements that auditors must follow when determining whether to accept or continue an engagement.

The guidelines, at their core, focus on ensuring that an engagement is only accepted when a firm can reasonably expect to complete it with professional competence, after appropriate due diligence and risk assessment.

With the recent adoption of the QC 1000, A Firm’s System of Quality Control, the PCAOB is making it crystal clear that client acceptance and continuation are critical components of a firm’s entire quality management system.

QC 1000, which has been postponed by one year to December 15, 2026, expands on PCAOB’s current guidelines to provide audit firms with a more risk-based quality control framework when they are deciding whether to accept or continue client engagements.

Rather than being simply a standard procedure, QC 1000 formalizes and elevates client acceptance and continuance procedures by embedding them into a more rigorous, documented, and continuously monitored quality control framework across the firm.

Firms may have an extra year before QC 1000 goes into effect, but early preparation is key to ensuring compliance and maintaining audit quality. That involves conducting a gap analysis of existing quality control systems, implementing enhanced client acceptance and continuance audit procedures, and leveraging the right tools and technologies.

PPC’s Guide to PCAOB Audits

A time-tested, proven audit approach designed to perform a public company audit under PCAOB standards

Shop book ↗

Identifying risks when accepting new clients

Not every engagement is the right fit. Being able to identify and assess risks upfront enables firms to make informed acceptance decisions and better safeguard audit quality and firm reputation. That’s why taking a disciplined, risk-based approach is key.

“I think one of the first things they [audit firms] need to do is some internal analysis on their own independence and capacity, and make sure they can do the work before they get too far … and then they need to do due diligence on the client,” said Alison Stephens, Executive Editor of PPC products for Thomson Reuters. “You need to make sure that this is somebody you want to be in business with. There’s a whole host of considerations; some of them come from the [PCAOB and AICPA] auditing standards and the quality management standards, and some of them are just common sense.”

To further break it down, firms must consider the following before taking on a new client:

Independence

Assess firm independence before accepting a new engagement. That includes reviewing any financial interests, prior services, or relationships that could impair firm independence, and determining if the client’s business could create a conflict of interest.

It is important to note that the AICPA recently sharpened and expanded its ethics interpretations to provide further clarity on rules and thresholds.

Stephens explained, “Something else to consider is the familiarity threat. Literally, you just know the client too well to exercise appropriate professional skepticism. … Also, fee considerations in proportion to your whole financial well-being. So, is one job paying for half of your firm’s existence? That’s a fairly new AICPA ethics interpretation. Are the fees disproportionate such that you’re not really independent?”

Integrity

Evaluate the integrity of the executive team. This entails performing background checks, looking for past legal or regulatory issues, and their history of financial statements. Does the client have a reputation for being transparent and compliant with laws and regulations?

Financial health

Analyze the company’s financial stability and cash flow. Are they under financial strain? Do they have a complex revenue model? Is it an industry with higher inherent risk, like financial services or healthcare?

Predecessor auditor communications

If the client had a previous auditor, auditing standards require successor auditors to communicate with the predecessor auditor (subject to client consent) before accepting a new engagement. Doing so helps the firm assess engagement risk. Questions to ask include: Does the predecessor auditor know of or suspect any fraud? Did they have disagreements with the client? Why is the company changing auditors? How long did they serve as the client’s auditor?

Due diligence red flags for auditors

Proper due diligence enables firms to identify risks as previously noted, and there are several red flags not to be overlooked. These include:

Opinion shopping: This technique prioritizes the client’s management’s preferred outcome, not only eroding trust and audit quality but also placing the firm at increased risk.

Litigation: Is the company facing any legal proceedings, and on the flip side, is the company litigious? Firms may not want to do business with a company that is known to sue its vendors or other associates.

Fraud allegations and criminal activity: If a company or its management has any past or present instances of fraud allegations or criminal activity, firms must tread carefully. The company may have new management in place to resolve any issues related to fraud and misconduct and restore integrity; however, if the prior management team remains in place, that is especially concerning.

Financial instability: Firms want to ensure they will make a reasonable return on an engagement. If a potential client is in financial distress, they may not have the ability to pay the audit firm for its services. Unpaid fees can also lead to independence issues for future engagements.

How audit leaders can handle client capacity

The PCAOB Code of Ethics requires that auditors not only be independent and objective, but they must also have the capacity and competence to perform a high-quality audit.

“You want to look at the industry itself. Do you have the industry expertise in-house? Is this a highly specialized area, and do you have people in-house who are going to be able to do this, or are there certain aspects of the business where you are going to have to hire a specialist? Which is fine if the engagement budget can bear that,” Stephens said.

Ensuring that the firm has the time to perform an audit properly is also essential, as auditing standards emphasize that engagement partners be involved and assume ultimate accountability for audit quality. That includes planning, supervision, and review of the engagement.

“The quality management standards are really specific about engagement partner responsibilities, and auditors get in trouble with peer review, they get in trouble in PCAOB inspections when there’s not enough supervision; when there’s not enough partner involvement,” said Stephens. “So, you need to make sure that your engagement partners have the bandwidth to do the work as well.”

A good way to gauge how long an engagement may take to complete is to refer to similar engagements the firm has done in the past, Stephens suggested.

Also, keep in mind that first-year audits often require more time and work, and a company undergoing its first-ever audit will also require more time and likely be labor-intensive.

Considerations for smaller audit firms

Smaller firms with fewer resources and strained bandwidth may be especially concerned about audit capacity, as well as competency. That said, there are measures they can take to help ensure success.

“If you want to grow your firm, you’re going to maybe have to step outside of your comfort zone. And you can do that. You can go into an industry that you’ve maybe never worked in before; you’ve just got to make sure that you have resources and training available, specialists available to make that transition. That’s how you grow,” Stephens said.

Smaller audit firms that are concerned about capacity may want to consider implementing a “scorecard” system. As the PCAOB highlighted in a recent edition of its Audit Focus, here’s how it works: points are assigned to a partner based on the number and type of audits already served. The higher the points, the higher the workload.

“The goal is to keep each partner’s workload at a level where they are below a certain points threshold and are therefore able to serve a new or existing engagement. Partners exceeding the point goal are required to discuss partner assignment with leadership to determine their capacity to take on another engagement,” PCAOB explained in the July 2025 edition of Audit Focus: Engagement Acceptance.

Client continuance and knowing when to end the relationship

Auditing and quality management standards require that firms reassess continuance at least annually, typically before planning begins for the next audit cycle. That enables firms to evaluate whether any conditions may have changed that might impair their ability to perform the engagement with independence, competence, and integrity.

That said, auditors also need to know when it’s time to end a client relationship should concerns or red flags arise. As Stephens outlined, such instances may include:

Management’s integrity becomes questionable. For example, the auditor finds evidence of fraud, misrepresentation, or the client demonstrates an unwillingness to provide information.

The client is unable or unwilling to pay the fees owed to the firm.

There’s been a change within the client or the audit firm that impairs independence.

How to manage audit client engagements with ease

Staying ahead in client acceptance and continuance doesn’t have to be an uphill battle. By combining a risk-based audit approach with the right technology, firms can streamline processes, mitigate risk, and confidently deliver a high-quality audit for engagements of all sizes.

Thomson Reuters is here to help with the technology and tools your audit firm needs to perform efficient and profitable audits that comply with professional standards and pass peer review.

Equip your firm for success and discover what’s shaping the future of audit leadership by exploring our new digital guide, “The 3 pillars powering the next generation of audit leaders.”

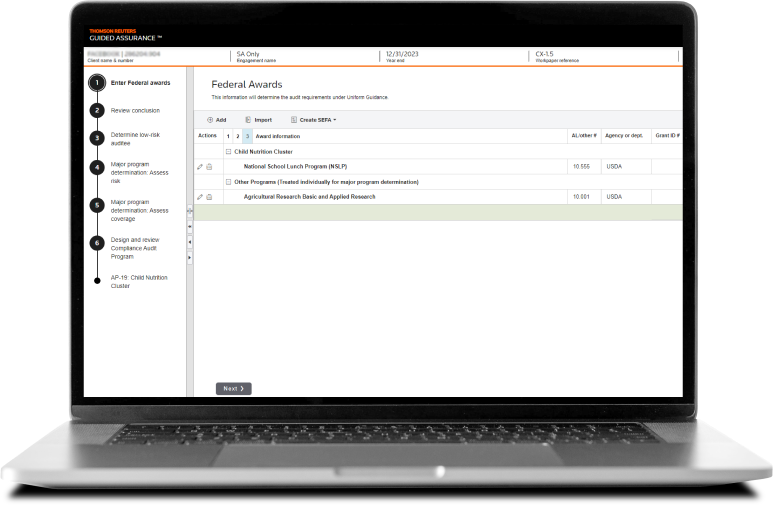

Guided Assurance

Design a risk-based audit approach for engagements of all sizes

Learn more ↗