Palantir Technologies has been described as a company that builds the kind of information infrastructure intelligence agencies would design if they had Silicon Valley’s best software engineers. Founded in the shadow of 9/11, the firm has grown into a critical provider of data analysis systems for governments and corporations around the world. Its platforms integrate fragmented, messy, and sensitive data on designated threats, transforming it into operational intelligence.

But Palantir’s technology is inherently Janus-faced. The same software that allows governments to defend against terrorism or respond to pandemics can also be deployed to monitor political opponents, quash dissent, and entrench authoritarian control. In this sense, Palantir represents a broader dilemma of the digital age: the dual-use character of advanced information infrastructure. Growing controversy surrounds Palantir, as the harmful potential of its work becomes increasingly evident.

This article examines the dual potential of Palantir’s capabilities. It traces the company’s origins, explains the architecture of its platforms, and evaluates how those systems can be constructive in outward-facing defense or destructive when turned inward against domestic populations.

Origins

Palantir was founded in 2003 by Peter Thiel, Alex Karp, Stephen Cohen, Joe Lonsdale, and Nathan Gettings. The company’s earliest funding came not just from venture capital but from the CIA’s investment arm, In-Q-Tel, reflecting its intended role in national security. The name itself, borrowed from Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, refers to “seeing stones” — a metaphor for omniscient observation.

From the outset, Palantir diverged from Silicon Valley’s consumer-tech model. Instead of seeking millions of users, it cultivated a small set of highly sensitive clients: intelligence agencies, defense departments, and later, major corporations. Its development model centered on embedding “forward deployed engineers” within client organizations. These engineers tailored Palantir’s platforms to messy, real-world data environments, effectively co-developing solutions on site.

This model carries profound dual-use implications. Close integration with state institutions means Palantir’s systems inherit the missions and priorities of their users. When deployed in democratic contexts for external defense, they can serve protective functions. But embedded within domestic security organs, they can equally serve to normalize mass surveillance and political control.

Palantir Technical Architecture

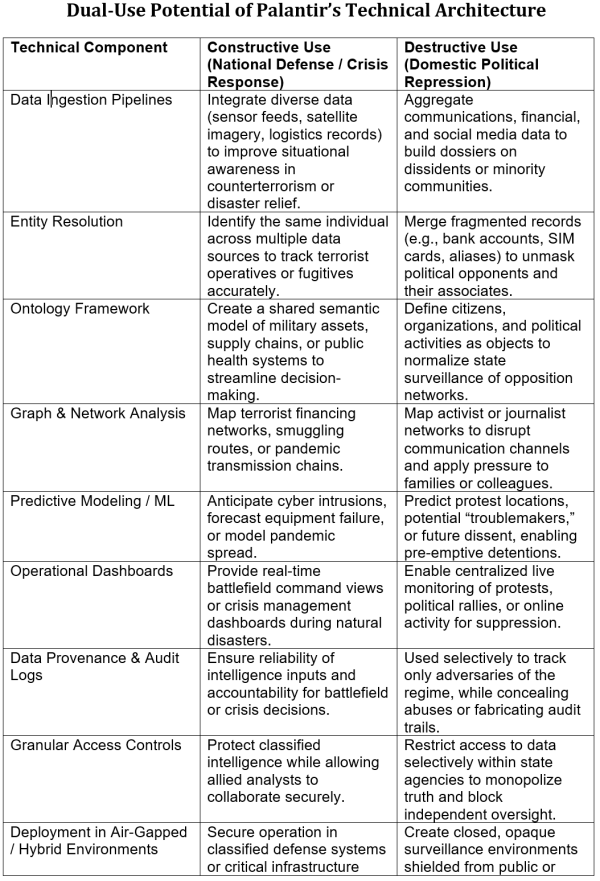

At the heart of Palantir’s duality is a technical architecture that is itself neutral. The product platforms are designed to ingest, harmonize, analyze, and operationalize heterogeneous data, regardless of its source or intended application. The architecture of the Palantir Gotham platform, sold to defense and intelligence clients, incorporates these key features:

Data Ingestion Layer – Capable of absorbing structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data from sensors, databases, documents, and social media feeds. Provenance and lineage are tracked to maintain auditability.

Ontology Framework – Provides a semantic model that maps raw data into objects (entities) and relationships, enabling analysts to work at the level of real-world concepts rather than tables and fields.

Analytical Layer – Supports graph analytics, machine learning pipelines, and scenario modeling. Users can search across silos, uncover hidden links, and test “what if” scenarios.

AI Integration – Embeds machine learning pipelines and interfaces (including Palantir AIP) for predictive modeling, natural-language queries, simulation of scenarios, and real-time decision augmentation.

Operational Layer – Offers dashboards, collaboration tools, and alerts to translate analysis into decisions and actions in near real time.

Security and Deployment Model – Enforces granular access controls, maintains detailed audit logs, and can run in classified, air-gapped environments or modern cloud infrastructure.

These components are not intrinsically beneficial or malign. They provide capabilities. Whether they serve as a guardian of national security or as a tool of political repression depends entirely on how governments choose to deploy them.

Business Model: Integration with Clients in Price-Insensitive Niche

Palantir departs from the standard software-as-a-service model. Instead of selling turnkey licenses to a broad market, it secures long-term contracts with a narrow set of high-value clients: governments, militaries, and major corporations. Its engineers, known as forward deployed engineers, embed directly within these organizations, adapting the platform to fragmented, often classified data environments and co-developing operational workflows with client personnel.

The cleverness of this strategy lies in targeting domains that are intrinsically not price sensitive. For intelligence agencies, defense departments, and crisis-response institutions, the stakes are existential: terrorist attacks prevented, wars won, pandemics contained. In such contexts, effectiveness matters far more than marginal cost. By combining a generic ontology-driven architecture with domain-specific tailoring and embedded engineering, Palantir makes itself indispensable at the command layer of decision-making institutions.

This model arose because the environments where Palantir operates—classified networks, fragmented legacy systems, ad hoc intelligence databases—cannot be standardized from the outside. Instead, engineers must adapt Palantir’s ingestion pipelines and ontologies to the unique data landscape of each client.

This close integration is both the strength and risk of Palantir’s model. It ensures the platforms are highly tailored and operationally relevant, but it also means Palantir becomes deeply entangled in the objectives and methods of its clients. If those objectives shift from defending national security to repressing dissent, the technology follows along—its dual potential realized not in abstract but in lived governance.

Palantir in Gaza

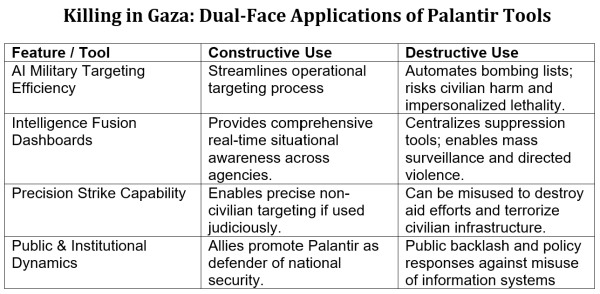

The consequences of Palantir’s dual-use potential are nowhere more visible than in the war in Gaza. Palantir platforms offer Israel’s defense establishment the ability to integrate vast amounts of intelligence data, generate a unified operational picture, and support military decision-making against a non-state adversary. However, these same tools are implicated in a campaign that has drawn widespread condemnation for disproportionate civilian harm and potential violations of international law.

Palantir’s role in Israel has been formalized through a 2024 strategic partnership with the Ministry of Defense. Its platforms reportedly assist in consolidating sensor data, drone surveillance, satellite imagery, and intercepted communications into shared operational dashboards. In principle, such capabilities can enhance the precision of military action, allowing commanders to discriminate between combatants and non-combatants and reduce operational blind spots. For a state confronting irregular adversaries who conceal themselves in dense civilian environments, the ability to fuse data into a coherent ontology is a critical defensive advantage.

Yet the same integration that improves military effectiveness can also facilitate targeting practices that raise serious ethical and legal concerns. Independent investigations have described the use of AI-assisted systems such as “Lavender” and “Gospel” by Israeli forces to generate thousands of strike recommendations at a pace previously impossible.

Although these systems were developed within Israel, Palantir’s platforms can serve as the infrastructure layer enabling their integration into broader intelligence workflows. The result, according to critics, is a system that automates the expansion of target lists, blurs human accountability, and facilitates the scale of bombardment witnessed in Gaza.

Reports of strikes on marked humanitarian convoys and medical facilities raise the question of how tools designed for intelligence precision can be turned toward suppression of civilian relief. UN experts and human rights groups have named Palantir among the companies “profiting from” the conflict by supplying AI capabilities that underpin operations in Gaza. Investor responses, such as the divestment by Norway’s Storebrand, highlight how corporate entanglement in contested wars can damage both ethical credibility and shareholder value.

Palantir’s Gaza involvement illustrates the dual-use paradox in sharp relief. The ontology-driven architecture and embedded engineering model that make its platforms indispensable for counterterrorism also make them adaptable to rapid, large-scale target generation in urban warfare. The same dashboards that can coordinate relief logistics in a natural disaster can orchestrate bombing campaigns. In Gaza, Palantir’s role is not hypothetical—it is a live demonstration of how data infrastructure can be simultaneously protective and destructive, depending on the political choices of its client.

The Domestic Risk of Misapplied Palantir Technology

Palantir’s platforms were born in the crucible of post-9/11 counterterrorism, but their architecture is not bound by mission. The same data ingestion pipelines, ontologies, and dashboards that help analysts track insurgent networks abroad could be redirected inward against a state’s own population. In the United States, where Palantir already provides tools to agencies such as ICE, the FBI, and local police departments, the risk of misapplication is more than theoretical.

If applied in a context of political polarization or authoritarian drift, Palantir’s systems could enable:Mass Surveillance of Dissent: Integrating phone metadata, financial transactions, and social media into persistent profiles of activists, journalists, or political opponents.Predictive Policing of Protest: Using machine learning models to forecast where demonstrations will occur and who might attend, justifying preemptive crackdowns.

Network Suppression: Employing graph analytics to map the associates of targeted groups, widening the circle of intimidation and making political activity personally costly.

Enabling “Social Credit” Schemes: Applying selective sanctions, such as travel restrictions and employment blacklisting, to targeted individuals based on their political activities

Palantir’s powerful information management tools could thus be employed in an infrastructure of domestic political control. The very features Palantir markets as safeguards—granular access controls, audit logs, and secure provenance—are only as effective as the institutions and personnel that govern their use. In the absence of robust legal frameworks and independent oversight, these technical protections offer little defense against deliberate misuse.

Conclusion

Palantir’s technology can act as a national security shield, defending against external threats and crises. But without legal safeguards, it can just as easily become a cage, controlling domestic political life through sophisticated means of surveillance. The question is not whether Palantir has built powerful tools. The question is whether the United States and other nations can ensure that such tools remain only tools of defense against foreign threats, and not become instruments of domestic repression.