The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

@jrovner

@julierovner.bsky.social

Read Julie’s stories.

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

Congress appears ready to approve a spending bill for the Department of Health and Human Services for the first time in years — minus the dramatic cuts proposed by the Trump administration. Lawmakers are also nearing passage of a health measure, including new rules for prescription drug middlemen known as pharmacy benefit managers, that has been delayed for more than a year after complaints from Elon Musk, who at the time was preparing to join the incoming Trump administration.

However, Congress seems less enthusiastic about the health policy outline released by President Donald Trump last week, which includes a handful of proposals that lawmakers have rejected in the past.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call, Sheryl Gay Stolberg of The New York Times, and Paige Winfield Cunningham of The Washington Post.

Panelists

Sandhya Raman

CQ Roll Call

@SandhyaWrites

@sandhyawrites.bsky.social

Read Sandhya’s stories.

Sheryl Gay Stolberg

The New York Times

@SherylNYT

Read Sheryl’s stories.

Paige Winfield Cunningham

The Washington Post

@pw_cunningham

Read Paige’s stories.

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

Congress is on track to pass a new appropriations bill for HHS, with the current, short-term funding set to expire next week. The bill includes a slight bump for some agencies and, notably, does not include deep cuts requested by Trump. But with the administration’s demonstrated willingness to ignore congressionally mandated spending, the question stands: Will Trump follow Congress’ instructions about how to spend the money?

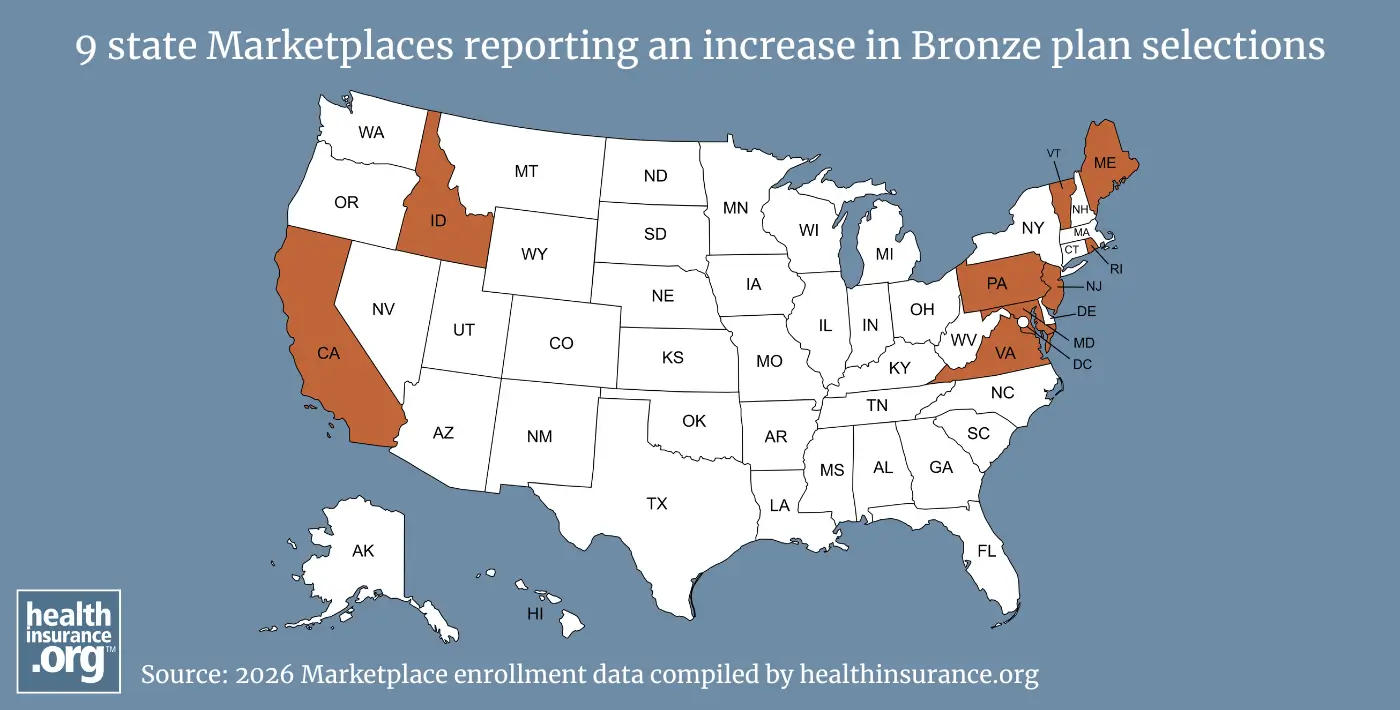

A health package with bipartisan support is set to hitch a ride with the spending bill, after falling by the wayside in late 2024 under pressure from then-Trump adviser Musk. However, the president’s newly released list of health priorities largely isn’t reflected in the package. The GOP faces headwinds in the midterms after allowing expanded Affordable Care Act premium tax credits to expire, a change that’s expected to cost many Americans their health insurance.

One year into the second Trump administration, its policies are particularly evident in the political takeover of the nation’s public health infrastructure, the growing number of uninsured Americans, and creeping brain drain in U.S.-based scientific research.

And Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has fired members of a panel overseeing the federal government’s vaccine injury compensation program. Kennedy is expected to remake the panel in an effort to expand the list of injuries for which the government will compensate Americans. The current list does not include autism.

Also this week, Rovner interviews oncologist and bioethicist Ezekiel Emanuel to discuss his new book, Eat Your Ice Cream: Six Simple Rules for a Long and Healthy Life.

And KFF Health News’ annual Health Policy Valentines contest is now open. You can enter the contest here.

Plus, for “extra credit” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: CIDRAP’s “Minnesota Residents Delay Medical Care for Fear of Encountering ICE,” by Liz Szabo.

Sheryl Gay Stolberg: Rolling Stone’s “HHS Gave a $1.6 Million Grant to a Controversial Vaccine Study. These Emails Show How That Happened,” by Katherine Eban.

Paige Winfield Cunningham: Politico’s “RFK Jr. Is Bringing the GOP and the Trial Bar Together,” by Amanda Chu.

Sandhya Raman: Popular Information’s “ICE Has Stopped Paying for Detainee Medical Treatment,” by Judd Legum.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: Health Spending Is Moving in Congress

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using transcription software. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello from KFF Health News and WAMU public radio in Washington, D.C. Welcome to What the Health? I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, Jan. 22, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast and things might have changed by the time you hear this. So, here we go.

Today we are joined via videoconference by Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Sandhya Raman: Good morning, everyone.

Rovner: Sheryl Gay Stolberg of The New York Times.

Sheryl Gay Stolberg: Hello, Julie. Glad to be here.

Rovner: And Paige Winfield Cunningham of The Washington Post.

Paige Winfield Cunningham: Hey, Julie.

Rovner: Later in this episode, we’ll have my interview with Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, whose new book, Eat Your Ice Cream, is both a takedown of the wellness industrial complex and a kinder, gentler way to live a more pleasant and meaningful life. But first, this week’s news.

So, and I don’t want to jinx this, it looks like Congress might pass a spending bill for the Department of Health and Human Services that will become law — meaning not a continuing resolution — for the first time in years. And attached to that spending bill, scheduled for a vote in the House today, is a compromise health extenders deal that was dropped from the final spending bill in 2024 and which we’ll talk about in a minute. But first, the HHS appropriations bill. Sandhya, what are some of the highlights?

Raman: So I think overall we just see a little bit of a slight increase for HHS compared to last year. Some agencies get a little bit of a bump: NIH [the National Institutes of Health], SAMHSA [the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration], HRSA [the Health Resources and Services Administration], Administration for Community Living. CDC [the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] is kind of the same as last year. But then we do see some cuts in some places. Something that was getting watched a little bit was refugee and entrant assistance, given some of the different national news related to refugees and immigrants, and so that’s getting cut by about a billion. And some of the back-and-forth there is, some conservatives wanted more than that, some Democrats didn’t want that to be cut. I think the big thing in health care that we were waiting on on this was whether or not they would prohibit NIH forward funding, which is something the administration has been pushing for, just giving out a lump sum for grants through NIH rather than over a multiyear period. And the concern the Democrats had on that was that if you’re doing the lump sum all at first, fewer groups would get money for research. And so there is a prohibition on that, on doing the forward funding.

Rovner: But just to be clear, the president, the administration, had asked for deep, deep cuts to the Department of Health and Human Services, and Congress is basically saying: Yep. Nope.

Raman: Yeah. I think even if you look at what the House had proposed last year, they had cut a lot of programs, or proposed to cut a lot of, and that was not there. I think a lot of times, what we’ve seen is that even in Trump 1, there’d be a lot more proposed cuts in their proposal, when the White House puts out their blueprint, and then Congress comes to more of a medium point, kind of similar to previous years. So I think that was something that a lot of the health groups had celebrated, that they weren’t going to get the steep cuts that they thought could be part of the process.

Rovner: Of course, the big question here is: Does the administration actually spend this money? We saw in 2025 them refusing to spend money, cutting grants, cutting off entire universities. And this is money that Congress had appropriated and that the administration is supposed to spend. Are they going to do it this time, is Congress? Have they put anything in this bill to ensure that the administration is going to do it this time?

Raman: There’s a little bit here and there on some of that. I don’t think there’s quite the sweeping things that some Democrats would have wanted to prevent some of that. Just last week, we had the back-and-forth with SAMHSA grants getting pulled and then unpulled. And so there’s a little language related to that in there, just because that was such a big 24-hour issue. And then education funding is coupled with HHS, and there there is specific language saying you can’t transfer the money that would be for education into another department to dismantle it. So—

Rovner: And, I would say, and basically, you can’t cut the Department of Education unless Congress says you can.

Raman: Yeah. So there’s some things in there that are like that, but to get appropriations done, it has to be a bipartisan thing to get that to the finish line. So no one is going to get everything they wanted, not even President [Donald] Trump.

Rovner: Yes, and I will point out that they are not there yet. The House has to pass this. The Senate has to pass this when they come back next week. We’ve got, apparently, a gigantic snowstorm coming towards Washington, D.C. So it’s moving in the right direction, but it’s not there yet. All right. Now onto the health package that’s catching a ride on this spending bill. What’s in it? And how close is it to the package that got stripped from the 2024 bill after Elon Musk tweeted that the bill was too many pages long?

Raman: I think it’s fairly similar. We have a lot of the same PBM [pharmacy benefit manager] language that we had when that got dismantled, and a lot of these same kind of extenders that we see from time to time whenever we get an appropriations deal, extending things that are pretty bipartisan but just never have a place to ride elsewhere — National Health Service Corps, Special Diabetes Program, things like that. I think that since this time we haven’t had that pushback, we don’t have Elon Musk weighing in and kind of pulling the strings in the way that we did before, these have been very bipartisan provisions that both chambers have been saying that they want to get this done, they want to get this done as soon as possible, even in the beginning of last year. So I don’t sense that something’s really going to derail language targeting PBMs and stuff like that.

Rovner: I would say the big piece of this is the deal that Congress came up with in 2024 to require more transparency on the part of these pharmacy benefit managers that everybody on both sides is accusing of pocketing some of the savings that they’re getting from drug companies and therefore making drug prices more expensive for employers and consumers.

Raman: So I think that this has been such a priority that this is their shot to get it done. And it seems like as long as nothing derails appropriations in the next day and a half, then this is their chance to do that.

Rovner: So what’s not in either of these packages are most of the pieces of the legislation that President Trump called for last week in his self-titled Great Healthcare Plan, with the PBM provisions being a major exception. What else is in Trump’s plan? And what are the prospects for passing it in pretty much any form this year?

Winfield Cunningham: I would say not great. Yeah. A couple of things that struck me about this plan, which I would note was one page long: This is very Trumpy. Trump obviously loves, he’s a lot more into hauling pharmaceutical CEOs into the White House to make deals than he is crafting detailed policy. Because if you’re actually trying to do health care reform, this is not the way that you would do it. What you would do is actually spend a lot of time on the Hill seeing what Republicans can sign onto, and working with staff to craft detailed policies and etc., etc. But, yeah, so most of this stuff — yet I guess another big thing that struck me was a lot of this actually goes after insurers. There are some things in here that drugmakers don’t like, but Trump goes so far as to propose bypassing insurers entirely and sending money to people. And of course he doesn’t detail how that would work. And then there’s a lot of stuff in here about transparency by insurers. I would note the Affordable Care Act had some insurer transparency provisions already.

So I think what this plan, if we want to call it a plan, reflects is just Trump’s desire to have something that he can call a “great” health care plan that he’s promised for a long time and which he’s going to talk a lot about. But yeah, I don’t think we’re going to see Republicans in Congress do much on this. Yeah, with the exception of the PBMs, which is pretty notable, and I think actually represents a really big win for the pharmaceutical industry, which has obviously felt under fire in this administration and has struck these deals with the White House, which they really don’t like. But they had been threatened that the administration would go further in trying to do this “most favored nation” price caps. And so it’s interesting because insurers are kind of Trump’s new target. That’s what I kind of read in this. And of course I would mention today that major insurers are testifying on the Hill because they’re under fire for raising insurance premiums.

Rovner: Although, as we’ve noted many times, they’re raising insurance premiums because the cost of health care is going up. Yes, Sheryl.

Stolberg: Julie, I think the political context of the Great Healthcare Plan, the so-called Great Healthcare Plan, is important. First of all, Republicans have had trouble for decades coming up with some kind of health plan, even before the Affordable Care Act was passed and signed into law in 2010. They weren’t able to do it then. President Trump famously said “nobody knew” that health care was “so complicated.” He’s in a situation now where Republicans have stripped many Americans of their health insurance by letting the extended Obamacare credits expire, and we’re going into a midterm election season in which his party and he have promised repeatedly that they were going to come up with a plan. He said he had a concept of a plan. I think this plan, so to speak, is not even a concept of a plan, and its primary provision actually lifts from what Sen. [Bill] Cassidy was promoting, which was to steer money away from insurance companies and toward consumers. Trump kind of latched onto that. He doesn’t say that explicitly in this 325-word proposal, but it seems clear to me that that is his idea, and that is just not a workable idea.

He wants, they want, to move money into health savings accounts. I cracked up my elbow earlier this year. I had surgery to repair it. I saw the bill. The bill was $122,000. I am very blessed to have good health insurance through my company. There is no way that the government is going to steer that kind of money into a health savings account for an uninsured person. These are accounts that are meant to be sort of supplemental to spend on relatively small expenditures. And if you are an uninsured person, there is really no way that you can cover yourself. And that’s basically what this so-called “great” American health care plan is proposing, which I suspect, if most Americans really looked at it, they would say, is not so great.

Rovner: Yeah. I also, I broke my wrist this summer. I also had surgery, although I had outpatient surgery, and it cost $30,000. So it’s, yeah, health care is really expensive, which, as I said, is why insurance premiums are going up. So, this week marks a year since the start of Trump 2.0, and it would take us the rest of the year to detail all that has changed in health policy. But I did want to hit a few themes, some of which you’ve started to talk about, Sheryl. One is the administration’s effort to basically end the federal public health structure as we know it. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta has basically been taken over by political appointees, most of them without health experience or expertise. Sheryl, you’re our public health expert here. What does it mean for public health to be basically ceded back to the states?

Stolberg: Well, I think this is kind of a novel experiment here. The core of the CDC is its infectious disease programs. Now, over the decades, since the 1970s, the CDC has greatly expanded its remit to cover things like chronic disease and gun violence prevention and auto safety, etc. But its core is infectious disease. And we know that infectious disease knows no borders. So what we risk having here is a patchwork of state-by-state vaccine recommendations, where some states will follow the CDC’s recommendations, presumably those that are red states. This was never political before. And we’re seeing some states, like blue states like New York and Massachusetts and other New England states, kind of coming together to put forth their own vaccine recommendations. I think this has implications for what vaccines will be covered and what vaccines will be offered by the Vaccines for Children Program, which was created by [President] Bill Clinton to cover poor kids and make sure they get vaccinated. I don’t think we know how that’s going to play out.

I saw [Health and Human Services] Secretary [Robert F.] Kennedy [Jr.] yesterday in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and he insisted that he’s not taking any vaccines away from anyone. If you want your vaccines, you can get them. But the truth is that for decades, the American public and the medical establishment have relied on the CDC to provide guidance. The CDC doesn’t mandate anything, but it provides really important guidance to the country, and the agency is crippled now. Its guidance is not going to be followed. And I think we’re in uncharted territory here. We’re already seeing measles is on the rise. The country’s about to lose its measles elimination status, which we acquired in 2000. Whooping cough is on the rise.

Rovner: Basically things we know we can prevent with vaccines.

Stolberg: Exactly, exactly.

Winfield Cunningham: One of the things I keep thinking about is, Kennedy says over and over again that if you’re a mom, you should do your own research. And it seems like a lot of the effects here is stepping away from this broad recommendation to now this patchwork of recommendations. So when you go to your pediatrician, you might hear guidance based on AAP’s [the American Academy of Pediatrics’] guidance, for example. States are doing different things. And as a parent, when you go to your pediatrician, it all of a sudden, I think, becomes a lot more confusing, especially if you’re someone who maybe already has a little bit of hesitancy about vaccines.

I was in with our pediatrician last week and asked her what they’re seeing, and people are coming in with a lot more questions. And interestingly, they actually are changing their policy for mandatory vaccines. They actually had required every patient to be up to date by age 2 with the CDC-recommended vaccines. Now those vaccines that are under shared clinical decision-making, they’re no longer going to require those. And it’s not, and they’re going to continue to recommend them, but I think they’re concerned that patients are going to come in and they’re saying: Hey, the CDC doesn’t necessarily recommend these now. I’m worried about them. So it’s put pediatricians in a difficult place. But, yeah, it’s, as a parent, you’re having to make a million decisions about your children, and this just kind of makes that more complicated and confusing, potentially, for parents.

Rovner: And takes time away from doctors who would like to counsel about other things, too.

Stolberg: I just want to add one thing about that. Kennedy says do your own research. And if you read the package inserts on a vaccine, you’re going to see that vaccines have side effects, just like any drug. But that information needs context around it, and the parents who are weighing those side effects need also to be told about the risk of the diseases that those vaccines are intended to prevent. And my kids are grown. I’m wondering how pediatricians are having that conversation, or if they’re having that conversation, in talking to parents about: These are the risks of the vaccine. But should your child get measles, these are the risks. Before vaccination was widespread for measles, 450 kids died on average every year. Many more were hospitalized. So I think those conversations need to be had.

Winfield Cunningham: And I think it’s hard for pediatricians sometimes to illustrate that, because we’re so far removed from people having examples or knowing anyone who had these.

Rovner: Not anymore.

Winfield Cunningham: Not anymore. But largely, right? I have a lot of parent friends, and I don’t know a child who’s had measles. Our pediatrician was telling me that when she was in medical school, it was still common for pediatric hospitals to be filled with babies with rotavirus. She said you could smell it down the hallway. And now, actually, the people in medical school, they’re not experiencing that, because of widespread vaccination.

Rovner: All right. Well, the second big thing I want to hit on is, as Sheryl already mentioned, people losing their health insurance. Last summer’s big budget bill would cut nearly a trillion dollars from the Medicaid program and make it more difficult for people to maintain their coverage through the Affordable Care Act. Republicans refusing to extend the expanded Affordable Care Act subsidies from the Biden era is already prompting people to drop coverage that they can no longer afford. What does it mean to the health care system as a whole that the number of Americans without health insurance is going to begin to rise again?

Raman: I think it’s a multipronged thing. There are some aspects of these things that might not be felt immediately, that might be later this year or early next year as different provisions of the [One] Big Beautiful Bill kind of come into play — work requirements, things like that that might affect how many people have insurance. But also, I think it kind of goes back to some of the things that Sheryl and Paige were saying about, just, if fewer people are vaccinated, it increases the risks for everyone. And if fewer people have health insurance, regardless of what they have, it also makes it more difficult. If people are not getting treated for things, they get exacerbated into more serious conditions. So I think there are a lot of issues at play. Some of them have just, we’re kind of waiting to see how the effects are.

You know, people that may have skipped out on ACA insurance this year, maybe they haven’t needed to go to the doctor yet. We’re in the first month. People might not go every month. But that doesn’t mean they’re not going to be hit with something big, even tomorrow, next month, month after that. And so I think all of these things kind of compound together to make it a lot more difficult of a situation, and just a lot of the complexities, I think it’s kind of in both of them where you’re not sure. Oh, is this renewed? Is this not renewed? It’s, I think, a lot more difficult for the average person to follow this national conversation as much as people that are really plugged in, so that by the time that it trickles down to them, it’s like: Can I sign up for health insurance still? Are the costs high? Am I still eligible? It gets more and more confusing. And then people who might be eligible might kind of be scared away with some of that chilling effect.

Stolberg: I should say, I think emergency rooms will also bear the brunt of the reduction in insurance, because without, people who don’t have health insurance will forgo going to the doctor until their [conditions are] unable to be ignored. And then they will wind up in the emergency room.

Rovner: And then those, I was going to say, and then those emergency rooms will end up passing the bills that they can’t pay—

Stolberg: Exactly.

Rovner: —onto others who can, or in—

Stolberg: Exactly. It will drive up costs—

Rovner: Paige, started—

Stolberg: —in the end.

Winfield Cunningham: I think a lot of this is going to become clearer over the next couple of months. We still don’t really know the effects of those extra subsidies expiring. I was actually surprised to see that the ACA marketplace enrollment figures they released, I believe last week, were not actually that much lower than last year. But people aren’t kicked off their plan until they haven’t paid their premium for three months. So I think we need to wait until April or so to see how many people were, say, auto-enrolled in a plan which they can no longer afford, and now they’re kicked off. And maybe it’s fewer people than we think. Maybe it’s more people than we think. But I think we just don’t know that yet, and we’re going to have to wait for a couple months to see.

Rovner: Yeah, I think you’re exactly right. I had the same reaction to seeing those numbers. Like, Wow, those are pretty high. And then it’s like, yeah, but those aren’t necessarily people who’ve had to pay their bills yet. Those are just the people who I think may have signed up hoping that Congress was going to do something. So, yeah, we will have to see how many people, I think it’s called “effectuated enrollment,” and we won’t get those numbers for a little while.

Well, finally, dismantling the federal research enterprise. As I said, we’ve talked about this a lot, but I didn’t want to let it sort of go unstated. This administration appears to like to keep people guessing by cutting and then restoring research grants, refusing to spend congressionally appropriated funding until they’re ordered to do it by the court, and firing or laying off workers only to call them back weeks or months later. All that makes it difficult or impossible for researchers and universities to plan their projects and personnel needs. Combined with new limits on federal student loans for a lot of graduate students, are we at risk of losing the next generation of researchers? We’re already talking about seeing people moving to Europe to continue their research.

Stolberg: Yes. I think the answer to that is an unequivocal yes. I am hearing from scientists who are having trouble filling their postdoctoral slots. Or young scientists. It’s really the next generation, right? People who are here already and who have families are trying as best they can to sort of stick it out, or maybe they’ll go into industry if they have to leave academia because they’ve lost their grant funding, or if they’ve left NIH. But it really is the next generation of researchers. I hate to draw this comparison, but we did see during World War II, the United States absorbed a lot of European researchers. This is how we got Albert Einstein, right? So I don’t know that we’ll see necessarily a reversal of that, of scientists fleeing, but we might see more young people choosing not to go into academic biomedicine.

Rovner: And we’re already seeing, it’s not just Europe. It’s China and India—

Stolberg: Yeah. Right.

Rovner: —offering packages.

Stolberg: And they’re recruiting. Those countries are recruiting. Yeah, they’re recruiting young scientists, especially China.

Rovner: Yeah.

Stolberg: And that’s a good point. David Kessler, the former FDA [Food and Drug Administration] commissioner, has argued that this is really a national security threat for the country. China is a main adversary of the United States, certainly of President Trump. And if we’re at risk of losing highly qualified biomedical researchers to China, then we are giving them an advantage.

Rovner: Yeah, something else we will keep an eye on, I think, for the rest of the year. OK, we’re going to take a quick break. We will be right back.

Meanwhile, back to this week’s news. The American Academy of Pediatrics is leading a coalition of public health groups that are suing to reverse the changes to the childhood vaccine schedule made by the CDC earlier this month. The suit claims that the administration violated portions of the law that oversees federal advisory committees that require membership on those panels to be, quote, “fairly balanced,” and not, quote, “inappropriately influenced.” Among other things, the lawsuit asked the court to ban the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices from further meetings. That would basically stop any further changes to the vaccine schedule, I assume?

Raman: At the end of the day, what ACIP does is just a recommendation to CDC, and they can choose whether or not to go with that recommendation. So I’m not really sure what would happen next, but it is kind of a whack-a-mole situation where just because you stop this does not mean that changes above that aren’t going to happen.

Stolberg: Yeah. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is just that. It’s an advisory committee. So this lawsuit takes issue with appointments to that committee and also complains that the committee was not consulted before the decision was made public to change the vaccine recommendations. I’m not exactly sure what the legal authority is for that. There’s apparently a federal law requiring federal advisory committees to be, quote, “fairly balanced” and not “inappropriately influenced.” But this isn’t — it’s an executive action — right? — to appoint committee members. It comes out of the executive branch. So I don’t know of any situation in the past where the judiciary has weighed in and said, You can appoint these people or not these people, or You have to redo a committee. So it’s hard to predict what the courts will say about this.

Rovner: Meanwhile, it’s not just the ACIP that HHS Secretary RFK Jr. is taking aim at. Following his remaking of that advisory committee, he’s now fired some of the members of a separate panel, the Advisory Commission on Childhood Vaccines, which oversees the federal Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which Kennedy has said he also wants to revamp. That’s the program that compensates patients who can demonstrate injury from side effects of vaccines. How big a deal could this be if he’s going to go after the vaccine compensation program?

Stolberg: Julie, this is a big deal, and I’ll tell you why. That committee sets what is known as the table of vaccines. Which injuries does the federal government compensate for? And the federal government does not compensate for autism as a vaccine injury. And I have no evidence of this, but if I were betting, that is where Kennedy wants to go. He does not like the 1986 law that created the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program because it offered liability protection to pharmaceutical companies. He wants to strip away the liability protection, but as I understand it, he does not want to do away with the law. He does not want to do away with the compensation program. So he may be trying to lay the foundation for the compensation program to be more expansive and cover injuries or allow claims for injuries that are not currently considered vaccine injuries, like autism.

Rovner: Which of course would collapse the program because it’s paid for by an excise tax on vaccines. That was the original deal back in 1986. The vaccine manufacturers said: We’ll pay you this tax, from which you, the federal government, will determine who gets compensated. And in exchange, you’ll relieve us of this liability, because we’re getting sued to death. And if you don’t do this, we’re going to stop making vaccines entirely. That was the origin of this back in 1986. And I was there. I covered it.

Stolberg: Yeah, exactly. I have read a lot of this history, and the CDC was really over a barrel. The companies were writing to CDC, saying, We’re going to pull the plug on our vaccines. And the CDC was worried that American kids were going to go without lifesaving vaccines because companies were going to quit making them. So they pushed this bill. [President Ronald] Reagan didn’t like it. He signed it into law anyway. And it’s created this program, which is actually imperfect. A lot of people who actually legitimately have vaccine-injured children have trouble getting compensated through this program., and I think many people on all sides of this issue would say that it does need to be overhauled. But it will be interesting to see who Kennedy picks for those committee slots.

Rovner: Yeah, I think we’re going to learn a lot more about it. We’re going to learn a lot more about it this year. Well, finally, in vaccine land this week, Texas attorney general and U.S. Senate candidate Ken Paxton on Wednesday announced what his office is calling a, quote, “wide sweeping investigation into unlawful financial incentives related to childhood vaccine recommendations.” His statement says that there is a, quote, “multi-level, multi-industry scheme that has illegally incentivized medical providers to recommend childhood vaccines that are not proven to be safe or necessary.” Actually, one of the reasons that Congress created the Vaccines for Children Program back in the 1990s, Sheryl, as you mentioned earlier, is because most pediatricians lost money on giving vaccines. And today, many people can’t even get vaccines from their doctors, because it’s too expensive for the doctors to stock them. What does Paxton think he might find here?

Stolberg: This is like stump the panelists. No one knows.

Rovner: I see a lot of people’s—

Raman: I’m not sure what he thinks he might find, but I do think that he is one of the attorneys general that is generally on the forefront of trying things, to throw spaghetti at the wall and see if it sticks on a variety of issues. So it might be the sort of thing where if he finds something, then it could be kind of a jumping point for other conservative attorneys general. And of course just that he’s primarying Sen. John Cornyn for Senate, so if it raises his profile for more folks. But I’m not sure if there’s a specific thing that he’s looking for.

Rovner: So he’s trying to curry favor with the anti-vaxxers in Texas, of which we know there are a lot.

Raman: That would be my best read.

Stolberg: Austin is, actually, the state capital in Austin is a hot spot for anti-vaccine activism. Andrew Wakefield, who wrote the 1998 Lancet article that’s been retracted, is in Austin. Del Bigtree, who runs the Informed Consent Action Network, is in Austin. There’s a group that I have written about called Texans for Vaccine Choice that is one of the early parent-driven groups seeking to roll back vaccine mandates, is based in Austin. So there’s a lot of sentiment there that Ken Paxton might be trying to appeal to.

Rovner: See? You’ve answered my question. Thank you. All right, that is this week’s news. Before we get to my interview with Dr. Zeke Emanuel, a couple of corrections from last week. First, I misspoke when I said House Republicans were becoming a minority in name only. Of course, I meant they were becoming a majority in name only. I also incorrectly said the lawsuit that helped get the Title X family planning money flowing back to clinics was filed by Planned Parenthood. It was actually filed by the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union] on behalf of the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association. Apologies to all. OK, now we will play my interview with Dr. Zeke Emanuel about his new wellness book, and then we’ll come back and do our extra credits.

I am so pleased to welcome back to the podcast Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel. Zeke is an oncologist and bioethicist by training and currently serves as vice provost for global initiatives and professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania. He formerly worked at the National Institutes of Health before he helped write and implement the Affordable Care Act while his brother Rahm was serving as President [Barack] Obama’s White House chief of staff. Zeke’s latest book, Eat Your Ice Cream: Six Simple Rules for a Long and Healthy Life, is out now. Zeke, welcome back to What the Health?

Ezekiel Emanuel: Oh, it’s my great honor and pleasure.

Rovner: So I feel like the subtitle of this book could be How to Keep Yourself Healthy Without Making Yourself Crazy or Broke and that it’s a not so thinly veiled attack on what many of us refer to as the “wellness industrial complex.” What’s gone wrong with the wellness movement? Isn’t it good for us to pursue wellness?

Emanuel: It is good for us to pursue wellness. I think that there are probably three things that are seriously wrong with the movement. The first one is that they make wellness an obsession that you have to focus all your energy on, which is totally wrong. Wellness should be a habit that sort of works in the background while you focus on the really important things of life. I think the second thing is they tend to overcomplicate things. Part of that is they’ve got to send out an email every day or every other day. They’ve got to do a video, a podcast, what have you. And so they make it complicated so that they have something to report on. And the third thing is they make it oversimple. They’re reductionist. They talk about diet and exercise and sleep, and leave out other very, very important parts of wellness, maybe the most important part of wellness, which is your social interactions. And almost all these experts ignore it.

And the last thing I would say — I guess I have four points — the last thing I would say is they have huge conflicts of interest. The wellness industrial complex is between $1- and $2 trillion a year, depending on what you want to include in that bucket, which means that there’s lots of people chasing lots of money trying to sell you lots of crazy items. So there’s money to be had and Them thar hills and people make all sorts of exaggerations. I want to emphasize for your listeners, I’m selling nothing, absolutely nothing.

Rovner: I will say, I went to your book party. I’ve been to a lot of book parties over the years. Yours is the first one where I actually was not expected to buy the book. You actually gave the book away.

Emanuel: Yeah, I can’t stand that. Oh, I hate that.

Rovner: I would say, I assume you were making a point with that. I also ate the ice cream, which was very good.

Emanuel: Yes.

Rovner: I feel like your underlying message here is that it’s not enough to make yourself biologically healthy — you have to do things that make you happy, too. Is that a fair interpretation?

Emanuel: Yes, that’s a very fair interpretation. Look, if you’re going to do wellness right, you’re going to be doing it for years and decades of your life. You cannot will yourself to do something for decades. You can will yourself to do something for a few weeks and a few months, but then, unless it becomes a habit that you actually enjoy, you’re simply not going to continue to do it. And so if you want to eat well, you want to exercise, you want to have social interactions, you actually have to make them something that’s pleasurable for your life, something that you find meaningful, even. That’s, again, I think something that’s seriously missing from a lot of these wellness influencers, because they make a lot of wellness about self-denial, about: You should deprive yourself. You should fast. Maybe you should fast. That’s OK if you can do it and you can work it into your schedule. Actually today is one of my fast days, so I am working it into my schedule. But that’s not for everyone, and it’s not essential to wellness and living a long and happy life.

Rovner: So what are your six simple rules, in two minutes or less?

Emanuel: The first one is: Don’t be a schmuck. Don’t take unreasonable risks. Don’t climb Mount Everest. Don’t go BASE jumping. Don’t smoke. Don’t do a lot of other stupid things. The second is: Engage people. A rich social life is the most important thing for a long, healthy, and happy life, and having close friends who you get together with regularly, talk to every week, have dinners with, acquaintances, very, very important. And then casually talking to people who you happen to interact with, either when you get your coffee, you go to the grocery store, you go to the restaurant, you hop in an Uber or a cab. Those are very important social interactions that we tend to ignore and tend to downplay. The third rule is: Keep your mind mentally sharp. And there are important aspects of that. Don’t retire. Take on new cognitive challenges.

The fourth is: Eat well, and make sure you get rid of the unhealthy eating part and eat important, non-processed items. The fifth is: Exercise. Do the three kinds of exercise: aerobic exercise, strength training, and balance and flexibility with yoga. And the last one is: Sleep well. It’s the one you cannot will yourself to begin doing. You can only sort of prep the bedroom and then hope it happens.

Rovner: So this whole thing didn’t really need to be book length, but you spent a lot of time reviewing the literature on various aspects of health and wellness, like, you know, a scientist would. Are you trying to make a point here about the current state of science and how the public views it?

Emanuel: I am. I am a data-driven guy. I like data. I think when you have more than 3 million people that have been surveyed and followed in terms of social interactions and their impact on your wellness and your physical health, that’s worth noting, and it’s worth noting what those studies come to. And they all come to the same basic thing, which is you can reduce your risk of death and mortality in the subsequent six, 10, 12 years, depending upon the study, by about 20% to 30% by greater social interaction, more robust friendships. That’s a pretty impressive number, if you ask me. So I’m trying to emphasize the data and get people to understand and be motivated by the data. And I think I’m pretty clear about moments when I, say, interpret the data differently than a lot of other people do, because I think that’s part of science.

So, for example, the PSA [prostate-specific antigen] test. Most guidelines say you should get a PSA test. I’m against the PSA test because, yes, it will reduce your risk of dying from prostate cancer, but it does not reduce your overall mortality. I think I don’t much care what’s written on my death certificate. I care about the length and wellness of my life, and the PSA isn’t going to affect that. But others disagree, and then I’m very frank about those kind of disagreements.

Rovner: So in 2014 you rather famously wrote an Atlantic article called “Why I Hope To Die at 75.” Has writing this book changed your mind about this? And I will say, I’m only a year younger than you, so I have a stake in this, too.

Emanuel: No, writing this book didn’t change my mind. It did change some things that I do. I will say, what really changed my mind, to the extent that anything changed my mind, was covid and the idea of getting vaccines after 75, I think, is a good thing, especially if whatever’s going around is targeting older people. It seems easy to protect yourself, whether from the flu or something like covid, with a vaccine. So that, I have changed my mind. Researching this book made me put a little more emphasis on, for example, strength training, which I had not done a whole lot of, directly. I’d done it because I ride a bicycle and I strengthen my lower half, my quads and my hamstrings and my gluteal muscles, but I hadn’t really focused on the upper body.

Rovner: You should do Pilates. It’s great.

Emanuel: Noted.

Rovner: Zeke Emanuel. It is always fun to chat with you. And congratulations on the book.

Emanuel: Thank you, Julie. This has been wonderful and very rapid-fire, more rapid-fire than anyone, because you get right to the heart of things.

Rovner: Well, we have a lot more that we’re going to talk about this week. Thank you, Zeke.

Emanuel: Take care, Julie. Bye-bye.

Rovner: OK, we’re back. It’s time for our extra-credit segment. That’s where we each recognize the story we read this week we think you should read, too. Don’t worry if you miss it. We will post the links in our show notes on your phone or other mobile device. Sandhya, why don’t you go first this week?

Raman: My extra credit is called “ICE Has Stopped Paying for Detainee Medical Treatment,”and it’s by Judd Legum for Popular Information, his newsletter. And I thought this was really interesting, because, I think, for me, I look very much at HHS and major health agencies, but his piece kind of looks at how ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] has not been paying third-party providers for medical care for detainees since October and that ICE, last week, the agency kind of quietly announced that it would not be processing any of the claims for medical care until April of 2026. And so doctors are instructed to kind of hold on that. And that’s kind of a downward spiral of providers denying services to detainees because they know they’re not going to get paid for a while. And so I thought this was a really interesting piece looking at that.

Rovner: Yes, indeed. And kind of scary. Paige.

Winfield Cunningham: Yeah, mine is a piece in Politico called “RFK Jr. Is Bringing the GOP and the Trial Bar Together,” and it’s by Amanda Chu. And this really caught my eye because it was a look at how RFK’s demonization of food and pharma is motivating trial lawyers representing consumers who are saying they’ve been harmed by these products — one example, of course, is the lawsuit against the maker of Tylenol — and how this really kind of goes against where Republicans have usually been, against trial lawyers representing consumers who say they’ve been harmed by big, bad companies. And so, yeah, it was a really interesting look at that and just at how RFK’s kind of populist, pro-consumer streak has fueled all of this.

Rovner: The world indeed turned upside down. Sheryl.

Stolberg: So my extra credit is from Rolling Stone. The headline is “HHS Gave a $1.6 Million Grant to a Controversial Vaccine Study. These Emails Show How That Happened,” and it’s by Katherine Eban. She’s a terrific journalist. And this is about the study in Guinea-Bissau. When CDC pulled back its recommendation for children to be vaccinated at birth against hepatitis B, HHS gave this grant to these Danish researchers to conduct this study in Guinea-Bissau, which would compare vaccinated infants to unvaccinated infants. And there was a huge howl of protest. This study would never be done in this country. The idea of withholding a vaccine from an infant that has been proven to be safe and effective is highly unethical. It evokes memories of the Tuskegee study, in which government doctors withheld treatment for syphilis. So there was this huge uproar, and it turns out that the researchers who got the grant are these Danish statisticians who have a really questionable research history. And the story documents, through emails, how they got basically this no-bid grant by coordinating with some of Kennedy’s allies from his movement, from his vaccine advocacy days. And it was kind of an inside deal, basically. So I just think that this study has generated a lot a lot of complaints. I should say that the researchers have amended the protocol, and now I think they’re going to give shots to one group at age 6 weeks. But still, it’s a very problematic study, and the story exposes how it came to be.

Rovner: Yeah, it is quite the story. Well, I also have an immigration story. It’s from my former colleague Liz Szabo at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, and it’s called “Minnesota Residents Delay Medical Care for Fear of Encountering ICE.” And it’s not just undocumented people avoiding medical care, as Liz details. U.S. citizens with serious health needs are also scared of getting caught up in the ICE dragnet that’s now all around the city. And ICE officials have even been entering hospitals and other health facilities — which in previous years they had not been allowed to do. In the dead of winter in Minneapolis, with a particularly severe flu year, this is threatening to become a health crisis as well as an immigration crisis.

OK, that’s this week’s show. Before we go, it’s almost February. That means our annual KFF Health News Health Policy Valentine contest is open. Please send us your clever, heartfelt, or hilarious tributes to the policies that shape health care. I will post a link to the formal announcement in the show notes. As always, thanks to our editor, Emmarie Huetteman, and our producer-engineer, Francis Ying. A reminder: What the Health? is now available on WAMU platforms, the NPR app, and wherever you get your podcast, as well as, of course, kffhealthnews.org. Also as always you can email us your comments or questions. We’re at [email protected]. Or you can find me still on X, @jrovner, or on Bluesky, @julierovner. Where are you folks hanging these days? Sandhya.

Raman: On X and Bluesky, @SandhyaWrites.

Rovner: Sheryl

Stolberg: I’m on X and Bluesky, @SherylNYT.

Rovner: Paige.

Winfield Cunningham: I’m on X, @pw_cunningham, and Bluesky, @paigecunningham.

Rovner: We will be back in your feed next week. Until then, be healthy.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

Click here to find all our podcasts.

And subscribe to “What the Health? From KFF Health News” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, the NPR app, YouTube, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.