For much of the post-WWII era, the United States maintained a set of institutional boundaries designed to govern the use of military force. War was understood to be exceptional, geographically bounded, legally regulated, and publicly accountable. Intelligence agencies gathered and assessed information. Military forces fought wars under declared authority, subject to the laws of armed conflict. Covert action existed, but as a marginal and politically risky exception rather than a governing mode.

Over the past two decades, those boundaries have steadily eroded in the U.S. The result is not simply a more assertive national security posture, but a transformation in how force itself is authorized, exercised, and justified. War has become increasingly untethered from formal declarations, legal clarity, and public accountability. U.S. recourse to military action has become routinized as a permanent, flexible instrument of policy rather than an exceptional act requiring Congressional approval and legal restraint. This transformation reflects a convergence of growing secrecy, elastic legal authority, and institutional incentives that favor action over restraint.

Venezuela as example

The recent U.S. attack on Venezuela provides a useful illustration of this transformation. Public reporting and official statements have been marked by ambiguity: unclear operational roles, uncertain legal authorities, and a heavy reliance on deniability. Whether any particular operation ultimately proves lawful or unlawful is less important here than the fact that its legal basis, chain of authority, and evaluative framework are unclear by design.

When it is difficult to determine whether an operation falls under military authority, intelligence activity, law enforcement, proxy action, or some hybrid, the distinction between war and non-war has already begun to dissolve. The question is no longer simply what happened, but under which framework it would even be evaluated. The Venezuela attack shows U.S. force projection increasingly operating in gray zones, where secrecy substitutes for accountability and legal boundaries are treated as adjustable.

Armed Reaper drone – CIA asset?

Vanishing norms

Before the attacks of September 11, 2001, U.S. national security institutions operated, at least formally, within more clearly defined roles and constraints. Intelligence agencies focused primarily on collection, analysis, and influence. The military conducted overt operations under Title 10 of the U.S. Code, embedded in chains of command governed by the laws of war. Covert action existed, but it was episodic, politically sensitive, and treated as an exceptional departure from normal practice rather than a standing mode of force.

The post-9/11 environment altered that balance in a more subtle but more consequential way. The 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force did not openly declare a global or permanent war. Instead, it delegated to the Executive the authority to determine who constituted the enemy, without specifying geographic limits, temporal boundaries, or a mechanism for revisiting those determinations. That delegation, combined with the global framing of counterterrorism, created a durable framework for executive discretion untethered from defined enemies or clearly delimited conflicts.

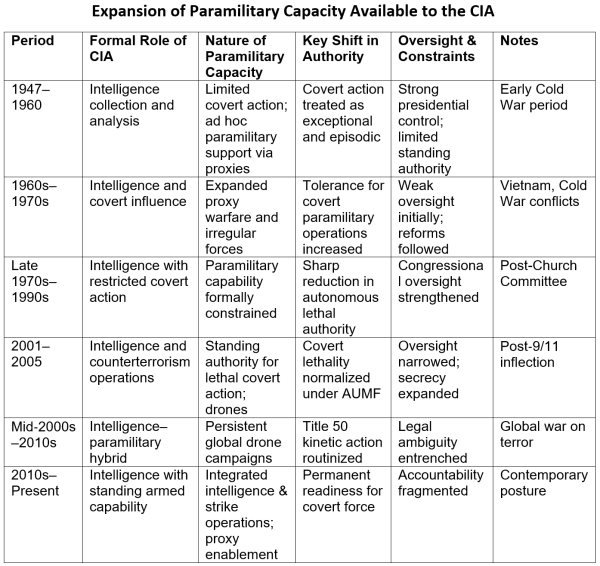

Over time, what began as an emergency response to a specific attack hardened into a standing framework for discretionary force. The Central Intelligence Agency, historically an intelligence and influence organization, acquired persistent access to paramilitary and kinetic capabilities through covert action authorities. Lethal operations that once required extraordinary justification became routinized. Geographic limits faded as the concept of a global battlefield took hold. Temporal limits disappeared as the conflict was treated as ongoing by definition rather than by circumstance.

This transformation was not the product of a single decision or an explicit repudiation of prior norms. It emerged through an accretion of precedents—each legally defensible in isolation, each justified as necessary adaptation, but corrosive in aggregate. As enemy designation, operational scope, and conflict duration migrated from legislative definition to executive determination, the boundary between exceptional wartime authority and ordinary governance steadily eroded.

Title 10 and Title 50 legal authorities

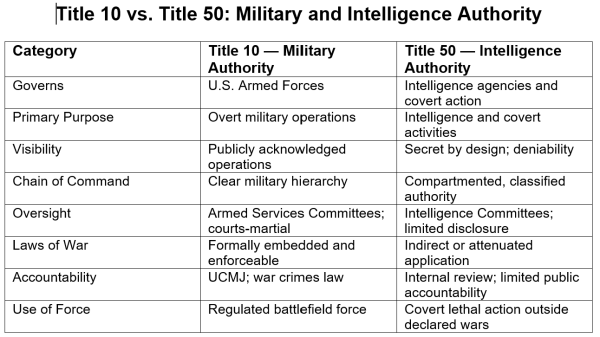

At the heart of this transformation lies in an important distinction between two sections of U.S. statutory law. Title 10 governs the armed forces. It presumes overt military operations, clear chains of command, enforceable rules of engagement, and formal adherence to the laws of armed conflict. Title 50 governs intelligence activities, including covert action, where secrecy and deniability are central by design and oversight is limited to select congressional committees.

The CIA’s founding statute did not envision the agency as an armed or war-fighting institution. Created by the National Security Act of 1947, the CIA was designed as a civilian intelligence organization focused on collection, analysis, and coordination. While the Act allowed the President to direct “other intelligence-related functions,” it assumed a clear separation between intelligence activity and the use of armed force, which remained the province of the military. The later expansion of CIA-directed lethal operations represents not the fulfillment of this design, but a departure from it—one that occurred without including the legal and ethical frameworks that govern warfare.

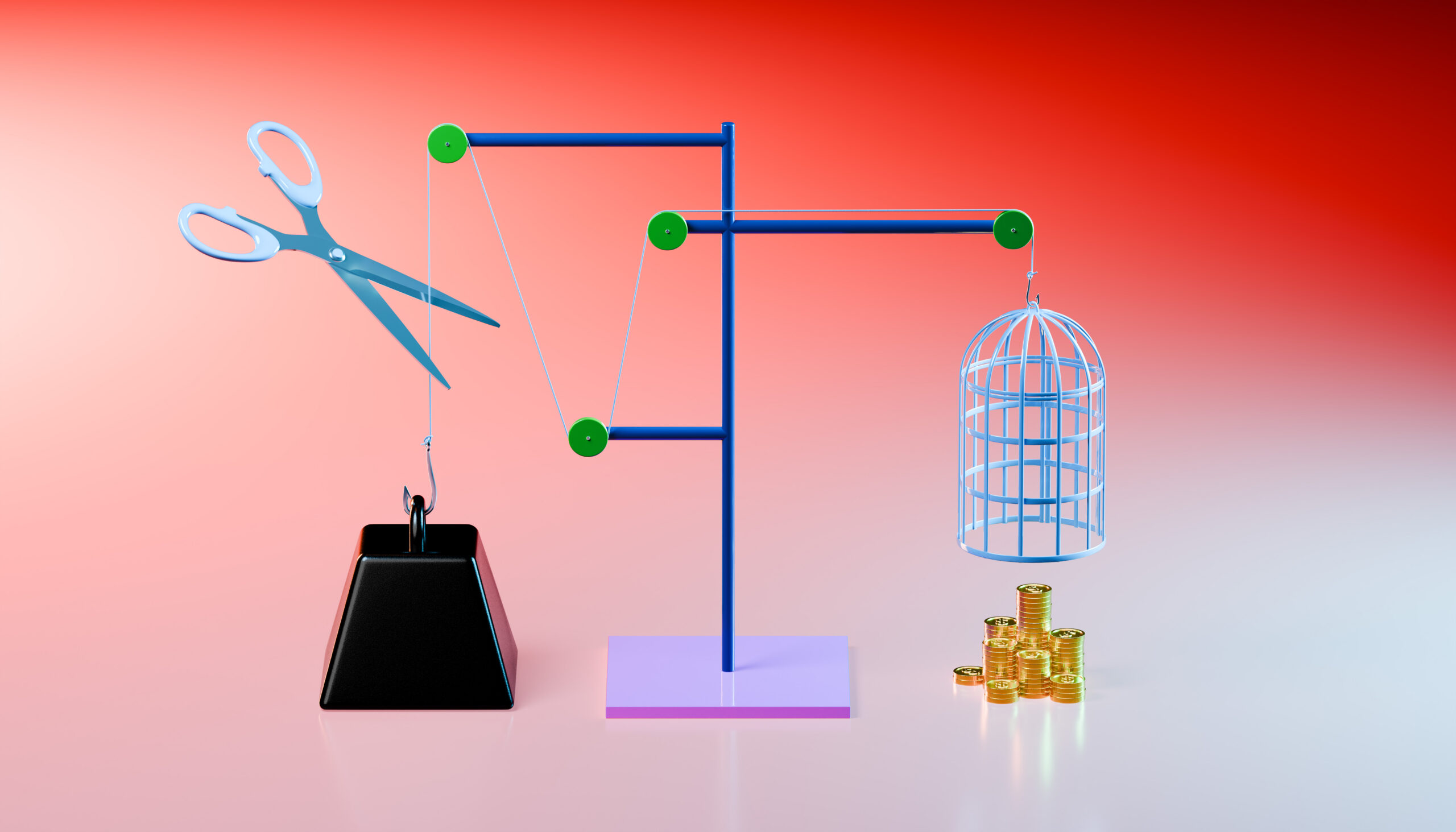

Both authorities are lawful. The problem arises when lethal force migrates from the Title 10 framework to Title 50 without carrying its normative constraints along with it. Under Title 10, the laws of war are not optional guidelines; they are structurally embedded through training, doctrine, and enforceable accountability. Under Title 50, those same norms are difficult to enforce in practice, even when formally acknowledged. From an operational standpoint, the shift can be subtle. The same personnel may operate in the same regions, using the same weapons, against the same targets. What changes is the legal wrapper—and with it, the mechanisms that make restraint meaningful rather than aspirational.

Converging Institutions

This authority migration has been reinforced by the growing convergence between intelligence agencies, elite special operations forces, and conventional military units. Over the past two decades, operational distinctions have blurred. Intelligence-led missions increasingly resemble military operations. Military units increasingly operate under intelligence authorities.

Elite military formations, such as units operating under Joint Special Operations Command, operate at the intersection of these frameworks. While their personnel are members of the armed forces and trained in the laws of war, their missions may be conducted under covert authorities designed for secrecy rather than battlefield accountability. Oversight fragments as operations shift between Title 10 and Title 50 regimes. The result is a gray zone in which responsibility is diffuse, attribution is contested, and restraint depends less on enforceable rules than on internal discretion.

This institutional convergence produces a greater hazard. When intelligence organizations possess standing kinetic authority, analysis itself is reshaped. Intelligence no longer functions solely to inform decision-makers; it becomes oriented toward enabling action. Evidence is evaluated through the lens of feasibility rather than restraint. Uncertainty becomes a justification for force rather than a reason for caution. Secrecy compounds this distortion. When decisions are insulated from external scrutiny, there is little corrective pressure to distinguish between intelligence assessment and operational advocacy. Even successful operations can degrade decision quality by reinforcing a system in which action validates analysis after the fact.

Erosion of the Laws of War

The laws of armed conflict function only when they are institutionally enforced. They rely on clear combatant status, transparent command responsibility, acceptance of surrender, and after-action accountability. Under Title 10, these requirements are explicit. For example, an order to “take no prisoners” would be unlawful, and U.S. service members are obligated to refuse it.

Covert lethal action undermines this structure not by openly violating the laws of war, but by sidestepping the conditions that make them operative. Intelligence agencies are not organized around battlefield transparency or public accountability. Their governing imperatives—secrecy, deniability, mission success—are fundamentally misaligned with the norms of military conflict. As covert lethality becomes normalized, legal exceptions accumulate. Over time, the exception becomes the rule, and restraint becomes discretionary rather than structural. The danger is not that war crimes are ordered, but that the bright lines preventing them fade from operational relevance.

Erosion of law at home

The implications extend beyond foreign policy. Institutional habits travel. Once normalized abroad, elastic authority, secrecy, and exceptionalism find analogues domestically in government surveillance, policing, and protest control. The boundary between external defense and internal governance weakens, not through conspiracy but through organizational drift. Militarism does not “come home” as a deliberate plan. It arrives as a consequence of government practices allowed to operate without oversight or legal limits.

Conclusion

Venezuela is not an isolated military operation. It is a symptom. The deeper danger lies in a national security system that conducts war outside the rules of war; exercises force without democratic constraint; and treats legal boundaries as adjustable rather than constitutive. Restoring restraint does not require abandoning security; it requires reasserting the institutional distinctions and safeguards that once made restraint enforceable. Without restoring clear distinctions between intelligence activity and war fighting; secrecy and accountability; and authority and legitimacy, the United States risks sliding into a condition of permanent war without boundaries.