For more than a decade, Americans have been assured—ritually and relentlessly—that the United States fields the most powerful military in history. This claim is repeated so often that it has acquired the status of self‑evident truth. It is invoked to reassure allies, deter adversaries, justify global commitments, and quiet domestic doubt. Yet beneath this triumphalist narrative lies a quieter, less comfortable reality: the U.S. military has been steadily shrinking in size, thinning in readiness, bloating at the top, and pricing itself out of mass and endurance. What remains is not a force optimized for sustained combat against a peer adversary, but one optimized for demonstration, reassurance, and bureaucratic self‑preservation. Much has been written about individual failures—procurement debacles, recruiting shortfalls, and readiness crises. But when examined together the problems of the U.S. defense establishment reveal not episodic mismanagement, but a systemic hollowing of capability masked by narrative inflation.

Shrinking force behind expanding claims

The long‑term decline in U.S. force structure is stark. At the height of World War II, the United States fielded thousands of naval vessels, hundreds of thousands of combat aircraft, and tens of thousands of armored vehicles. Today, the U.S. Navy operates fewer ships than it did before World War I, while combat aircraft and armored forces have fallen to a fraction of their Cold War levels.

The usual rejoinder is that modern platforms are so vastly more capable that fewer are needed. This argument collapses under wartime conditions. Precision does not eliminate attrition, software does not replace logistics, and exquisite systems fail just as surely as crude ones—often taking far longer to repair or replace.

WWII B24 bomber production – over 18,000 were built

Readiness: the harsh reality

If total inventories are troubling, readiness is worse. Across naval, air, and ground forces, only about half of nominal platforms are fully mission capable at any given time. The remainder are partially capable or non‑deployable due to maintenance backlogs, parts shortages, or deferred depot work. As a result, the effective operational force of the U.S. military is much smaller than its stated total capacity.

Readiness is increasingly propped up by cannibalization, crew overwork, and heroic maintenance efforts—borrowing capability from the future to meet present commitments. This is not resilience; it is fragility under stress.

Leadership inflation and accountability decay

As force size and readiness have declined, senior leadership density has grown. The ratio of flag officers (generals and admirals) to enlisted personnel has more than tripled since World War II. This reflects bureaucratization and risk aversion rather than operational necessity.

Major weapons program failures rarely end careers. Strategic misjudgments are absorbed into process language and rotational command structures, eroding the principle that authority entails accountability. In World War II, senior commanders were removed or sidelined when performance failed to match strategic need; today, generals linked to major U.S. military debacles advance upward, reflecting a system that rewards conformity and survival rather than results.

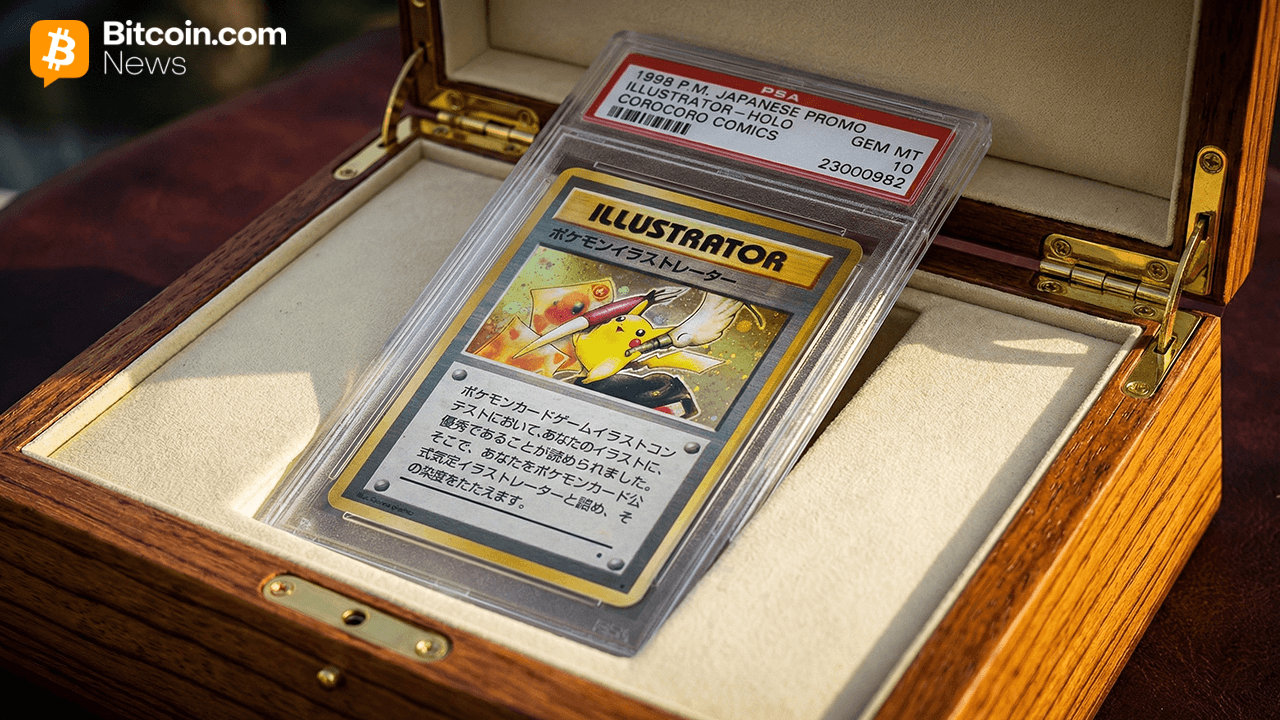

Cost explosion and shrinking mass

Modern U.S. combat systems have become catastrophically expensive. Inflation‑adjusted unit costs for ships, aircraft, and armored vehicles have exploded across every era. As unit costs rise, force size must fall—and attrition becomes strategically intolerable. A military that cannot afford to lose its own equipment cannot credibly threaten to fight a war.

F-22 stealth fighter – 750 planned but only 187 built

B-2 stealth bomber – 132 planned but only 21 built

Nuclear forces and the limits of substitution

Some will argue that nuclear forces render conventional force structure less relevant. This reverses the logic of deterrence. Nuclear weapons deter total war precisely because they make conventional miscalculation catastrophic. They do not compensate for weakened conventional forces; they raise the stakes of error when those forces are overextended or misrepresented. A hollow conventional military backed by nuclear weapons is not safer—it is more dangerous, because it narrows decision‑makers’ room for maneuver while increasing the cost of mistakes.

Advanced conventional weapons and the illusion of technological escape

Nor do appeals to advanced conventional technologies—hypersonic weapons, unmanned systems, artificial intelligence, or next‑generation platforms—rescue the prevailing narrative. In many of these areas, the United States has not established decisive technological advantage, and in some cases has fallen behind peer competitors in operational deployment. Hypersonic systems, long‑range precision strike, integrated air defenses, and large‑scale unmanned warfare have moved from experimental concepts to routine force elements elsewhere, while U.S. efforts remain fragmented, delayed, or confined to prototypes. Technological sophistication has thus become less a source of advantage than a compensatory story—one that further increases unit cost, reduces producibility, and deepens intolerance for loss. The result is not dominance, but a narrowing of real capabilities masked by claims of future superiority.

What now?

The natural response to this diagnosis is to ask what should be done. That question, however, assumes the problem is one of policy adjustment rather than structural constraint. In reality, there are only three paths forward—and none are comfortable.

1. Rebuild at scale.In theory, the United States could attempt to rebuild mass and resilience: accept lower technological ambition, cancel prestige programs, invest in industrial capacity, and prioritize quantity alongside quality. In practice, this would require decades of sustained political commitment, rebuilding of industrial capacity, restructuring of defense procurement, and a willingness to dismantle entrenched institutional incentives. There is no constituency for such a reset.

2. Shrink commitments to match capacity.A second option is to reduce global commitments to align with actual force structure: fewer forward deployments, explicit prioritization of theaters, and abandonment of universal deterrence. This approach is strategically rational but politically toxic. It looks like decline, offends allies accustomed to U.S. guarantees, and contradicts elite identity narratives. Yet it is the only option that genuinely reconciles ends with means.

3. Continue as we are.The third path requires no decision—and is therefore the most likely. It entails ever-greater rhetorical inflation, thinner operational margins, rising escalation risk, and increasing reliance on bluff. It does not end in sudden collapse, but in a steadily rising probability of catastrophic miscalculation.

The need for military pragmatism and accountability

The problem described here is not the result of a single bad program, administration, or strategic choice. It is the cumulative outcome of decades of incentives that reward technological ambition over producibility, narrative reassurance over empirical accounting, and career continuity over accountability. The result is a military optimized to deter on paper, posture symbolically, and reassure rhetorically, while quietly losing the capacity to deliver effective defensive and offensive capability. At this point, the realistic task is not rebuilding dominance, but governing risk under conditions of over-extension and illusion. That requires truthful force accounting rather than readiness theater; realistic prioritization rather than universal commitments; humility about escalation control; real accountability within the military institution; and narrative restraint in place of triumphalist reassurance.

Conclusion

The danger of shrinking military capability is not merely that the United States might lose a future war. It is that decision-makers, allies, and adversaries alike are being conditioned to believe that reserves of power and resilience exist where they no longer do. In such an environment, escalation becomes easier, restraint appears unnecessary, and risk is systematically mispriced. Nuclear weapons and advanced technologies do not mitigate this danger; they magnify it by raising the stakes of miscalculation while narrowing the space for recovery. History offers little mercy to great powers that substitute boastful narrative for material readiness. A military system that cannot tell itself the truth risks misuse and operational failure. A nation that mistakes posturing for power courts disaster.