Trump captured a sitting president and announced America would “run” Venezuela. The debate about legality misses what actually happened.

At 2 a.m. on January 3rd, U.S. military helicopters flew low over Caracas, firing at targets on the ground. By morning, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro was in handcuffs on a Department of Justice aircraft heading to New York. His wife was with him. The vice president who remained behind was told, according to Trump, that she “really doesn’t have a choice” but to cooperate.

At a press conference hours later, Trump was asked to justify the operation. His answer was remarkably direct: “The Monroe Doctrine is a big deal, but we’ve superseded it by a lot, by a real lot. They now call it the Donroe Doctrine.”

He continued: “American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again.”

I’ve been watching the coverage since then. Most of it focuses on legality. Whether the operation violated international law. Whether the narcoterrorism charges against Maduro are legitimate. Whether Congress should have been consulted. These are reasonable questions with obvious answers that won’t matter.

The actual story is simpler: the United States just stopped pretending.

What the pretense was

For 80 years, American foreign policy operated through what officials called a “rules-based international order.” The premise was that sovereignty meant something. That international law constrained what powerful nations could do. That the UN Charter represented genuine principles rather than convenient rhetoric.

This was always partially fiction. The U.S. wrote most of the rules. It enforced them selectively. It violated them when convenient and cited them when useful. But the fiction served a purpose. It created a framework that smaller nations could appeal to. It established limits—not on what the U.S. could do, but on what it would do openly. It maintained the possibility, however theoretical, that power required justification.

Guatemala 1954: the CIA overthrew a democratically elected government because it threatened United Fruit Company’s land holdings. But publicly, the operation was framed as fighting communism. Iran 1953: the CIA overthrew a democratically elected government because it nationalized oil. But the story was about Soviet influence. Chile 1973: the U.S. backed a coup against Salvador Allende. But the narrative was about protecting democracy from Marxism.

The violence was always there. The difference was the packaging.

When Trump invoked the Monroe Doctrine by name—a 19th-century declaration that Latin America belongs to the American sphere of influence—he wasn’t adding something new. He was subtracting something. The layer of justification that previous administrations maintained even when no one believed it.

The economic architecture underneath

To understand what actually happened on January 3rd, you have to understand something about how American power works that rarely makes it into the headlines.

The United States runs a $38 trillion national debt. Interest payments on that debt now exceed $970 billion annually—the second-largest federal expense after Social Security. The government spends more than $11 billion per week just servicing what it already owes.

Any other country with this debt profile would have collapsed into hyperinflation or default decades ago. The U.S. hasn’t. The reason is the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency—what French Finance Minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing famously called America’s “exorbitant privilege.”

Here’s how it works: because the world needs dollars to buy oil, settle international debts, and participate in global trade, there’s automatic demand for American currency. This demand allows the U.S. government to borrow at lower interest rates than any other nation, effectively financing its deficits by printing money that the world is compelled to use. It’s the economic equivalent of owning the toll booth on every major highway in the global economy.

The foundation of this system was laid in 1974, when Henry Kissinger negotiated an agreement with Saudi Arabia to price oil exclusively in dollars. In exchange for American military protection, the Saudis agreed that oil—the world’s most essential commodity—would be bought and sold in American currency. Other OPEC nations followed. The “petrodollar” was born.

This system has allowed the United States to run permanent deficits, fund its military, and maintain global dominance for 50 years. And it’s precisely this system that Venezuela threatened.

What was happening in the room

Here’s a detail that deserves more attention than it’s getting.

Hours before the raid, Maduro was at the presidential palace meeting with China’s special envoy, Qiu Xiaoqi. They discussed bilateral relations, strategic partnerships, the usual diplomatic pleasantries. Maduro joked about his zodiac sign. He didn’t look like a man who understood his time was running out.

Qiu was almost certainly the last foreign diplomat to see Maduro in power.

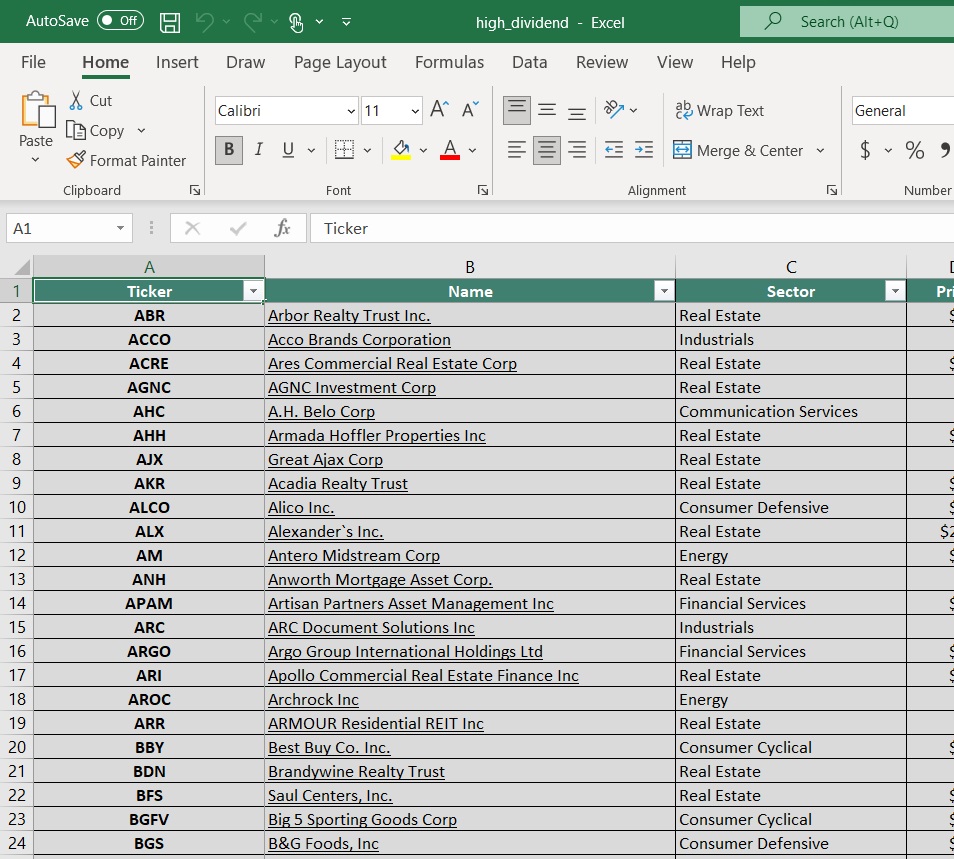

This wasn’t coincidence in any meaningful sense—Trump had apparently given the order days earlier, delayed only by weather and military logistics. But the symbolism matters. About 80 percent of Venezuela’s oil exports were going to China. And since 2018, Venezuela had been selling that oil in yuan, not dollars.

Venezuela had also been actively seeking BRICS membership—the economic bloc of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa that has been building alternative payment systems designed to bypass the dollar. Venezuela had established direct settlement mechanisms with China that bypassed SWIFT, the U.S.-dominated financial messaging system that Washington has weaponized through sanctions.

In other words: a country sitting on 303 billion barrels of proven oil reserves—the largest in the world—was actively building an economic architecture that excluded the United States entirely.

The historical pattern is unmistakable. In 2000, Iraq announced it would accept only euros for its oil; Saddam Hussein was removed from power three years later. Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi proposed a gold-backed pan-African currency to replace the dollar for oil transactions; NATO intervened in 2011. Iran has sold oil in currencies other than dollars since 2012 and faces continuous sanctions pressure and repeated threats of military action.

Venezuela is simply the latest chapter in this pattern—with one crucial difference: it had China’s economic backing.

What this is actually about

The raid wasn’t primarily about drugs. The narcoterrorism charges are a legal mechanism, not a motivation. It wasn’t about democracy—the U.S. has supported and continues to support plenty of authoritarians who serve American interests.

It was about this: as one Atlantic Council analyst put it, the operation creates “a once-in-a-generation opportunity” to ensure “extra-hemispheric powers like China and Russia are excluded from meaningful influence” in Venezuela.

In plainer language: this is our hemisphere, not yours. And more importantly: this oil will be priced in dollars, not yuan.

Trump announced that oil sales to China would continue—but under American supervision, with American companies taking control of the infrastructure. The largest proven oil reserves in the world, previously flowing to America’s primary competitor in a currency that wasn’t American, will now flow according to American interests.

The immediate threat was never that Venezuela alone would collapse the dollar. It was the precedent. If Venezuela could function outside the dollar system with BRICS support, other nations in America’s “backyard”—Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia—would have a template. The Western Hemisphere, long considered America’s uncontested domain, could pivot toward an alternative economic architecture.

That’s what was stopped on January 3rd.

What this breaks

The argument the United States has made for decades—against Russian aggression in Ukraine, against Chinese pressure on Taiwan, against Iranian influence in the Middle East—rested on a claim that the post-WWII international order meant something. That sovereignty wasn’t just a word. That powerful nations couldn’t simply absorb their neighbors or topple inconvenient governments because they had the capacity to do so.

That argument just died.

When Putin says Ukraine belongs to Russia’s sphere of influence, the U.S. used to respond: that’s not how the world works anymore. We have international law. We have the UN Charter. We have norms against wars of conquest.

When Xi Jinping says Taiwan is part of China and reunification is “unstoppable,” the U.S. used to invoke principles that transcend raw power.

Those responses are no longer available. Not credibly. As the New Statesman observed: Trump has “fatally undermined future US efforts to rally opposition to similar attempts at regime change elsewhere.”

The U.S. can still oppose Russian or Chinese expansion. But it can no longer claim to be defending a rules-based order against authoritarian revisionism. It can only claim to be defending American interests against competing interests. Which is precisely what Russia and China have always said they were doing.

What the world looks like now

The national security strategy the Trump administration released last month announced a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine. It explicitly authorizes intervention in Latin America to seize strategic assets, fight crime, or control migration. The strategy says comparatively little about Russia and China—leading critics to conclude that Trump is essentially acknowledging that they have their own spheres of influence.

This is the shape of the emerging order: three great powers, each with a “backyard” that it polices with whatever force it deems necessary. The United States controls the Western Hemisphere. China consolidates the Indo-Pacific. Russia asserts dominance over its near abroad.

The “rules-based order” becomes a legacy system—still cited occasionally, still technically operational, but no longer the actual operating framework for how power works.

Some will call this realism. An honest acknowledgment of how the world has always functioned beneath the rhetoric. And there’s truth to that. The pretense was always a pretense.

But pretenses have consequences. They shape what seems possible. They create frameworks that constrain behavior even when they don’t prevent it. They establish shared fictions that smaller nations can appeal to and that populations can invoke against their own governments.

What replaces the pretense isn’t clarity. It’s a world where the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must—and everyone knows it, and no one bothers to claim otherwise.

The dollar question

There’s a deeper irony here. The intervention may accelerate precisely what it sought to contain.

China won’t abandon its alternative payment systems. China’s Cross-border Interbank Payment System now connects over 1,700 financial institutions across 180 countries. BRICS won’t dissolve. The petroyuan will continue gaining traction among nations that now have fresh evidence of what happens when you remain dependent on the dollar.

As one analyst put it: “The Global South will not forget the lesson it has just witnessed. If anything, the takeaway is likely to be that diversification is safest when pursued collectively rather than individually. That insulation, not defiance, is the prerequisite for autonomy.”

The dollar’s share of global reserves has already declined from over 70% in 2000 to around 57% today. This isn’t collapse—the dollar remains dominant. But the trend is clear, and the raid on Caracas has given every finance ministry in the Global South a visceral reminder of why they should be building alternatives.

Venezuela was not invaded because the dollar is dying. It was invaded because the system that sustains American primacy can no longer rely on consent alone.

What I keep coming back to

I’m not going to tell you how to feel about Maduro. He oversaw the collapse of Venezuelan democracy, the exodus of eight million people, the immiseration of a nation that sits on unfathomable oil wealth. Many Venezuelans are celebrating in the streets. Their relief is real and legitimate.

I’m also not going to tell you that American intervention will lead to Venezuelan flourishing. The track record isn’t encouraging. When the U.S. “runs” countries, the outcomes tend to serve American interests, not local populations.

What I keep coming back to is simpler: Trump said out loud what the system actually is. Not what it claims to be. What it is.

“American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again.”

That’s not a justification. It’s not an argument. It’s a statement of fact backed by force. And once you hear it clearly, you can’t unhear it.

The world didn’t change on January 3rd. The mask slipped. What was always there became visible.

Whether that visibility changes anything—whether seeing the system clearly creates any obligation to act differently within it—is a question I can’t answer for you. I can only tell you what I see.

The pretense is over. The competition between great powers is now openly a competition. The rules apply to those without the power to break them. And underneath it all, the question that actually matters: whose currency will price the oil that runs the world?

That’s the story. Everything else is commentary.