Tens of millions of Americans who receive food assistance have been in danger of losing those benefits as the government shutdown crawls into its second month. But Friday brought a potential lifeline: A federal court ruling ordered the Trump administration to release emergency funds for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

On Friday, Judge John J. McConnell, of the U.S. District Court for the District of Rhode Island, ruled that the Trump administration must release funds from the $5.5 billion SNAP contingency fund and other potential pots of money in order to keep the program going. The contingency fund is meant to be tapped in emergency situations.

The White House recently claimed that the contingency fund could not be used to fund regular SNAP benefits. McConnell sided with a coalition of cities and nonprofits suing the federal government over the potential lapse. In his ruling, McConnell said “there is no doubt, and it is beyond argument, that irreparable harm will continue to occur.”

Also on Friday, Judge Indira Talwani, of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts, ordered the Trump administration to signal, by Monday, whether it would provide SNAP benefits in November. The case Talwani considered was brought forth by two dozen states and the District of Columbia that sued the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts, alleging that the department is violating federal spending laws by not releasing SNAP contingency funds to avoid a funding lapse. On Thursday, during the case hearing, Talwani said, “Congress has put money in an emergency fund, and it is hard for me to understand how this is not an emergency.”

During the 2018-2019 shutdown — under the first Trump administration — the USDA told states they could use the contingency funds to issue February 2019 benefits early.

Even with McConnell’s order, there will likely be a delay in SNAP benefits distribution due to the administrative process of allocating funds to EBT cards. And if the administration does not find money from pools beyond the contingency fund, there could still be a lapse later in the month: SNAP needs $9.2 billion in funding to pay benefits through the entirety of November. Experts say the administration can transfer money from other funds to continue payments through the end of the month.

What happens when SNAP funds run out?

When the emergency funds run out, millions of Americans will no longer receive food assistance from the federal government — and that will continue to be the case until the government shutdown ends. It would mark the first time in the program’s history that SNAP benefits have been delayed for all participants.

There will be immediate effects on people and lasting ripple effects on the economy from the benefit lapse:

Millions of households already struggling to afford food will lose access to federal food assistance. If the shutdown goes on long enough, some 41.7 million people will be without SNAP. That’s about 12.3% of the U.S. population, according to the USDA.

Food banks, which were strained before the shutdown, will have more difficulty meeting demand, especially in areas with high concentrations of federal workers and SNAP recipients.

Without SNAP, grocery stores and other retailers that accept SNAP through electronic benefit transfer (EBT) payments will take a hit, resulting in declining sales and less economic activity.

When the shutdown ends and SNAP benefits are restored, a sudden increase in demand could put added pressure on supply chains and potentially push food prices up.

“Families should never have to wonder if they’ll be able to buy groceries because of politics,” says Gina Plata‑Nino, interim SNAP director at the nonprofit Food Research & Action Center (FRAC).

How much does SNAP provide?

The typical SNAP participant receives about $187.20 per month, according to FY 2024 data from the USDA. The amount a participant gets each month varies by income level and other factors.

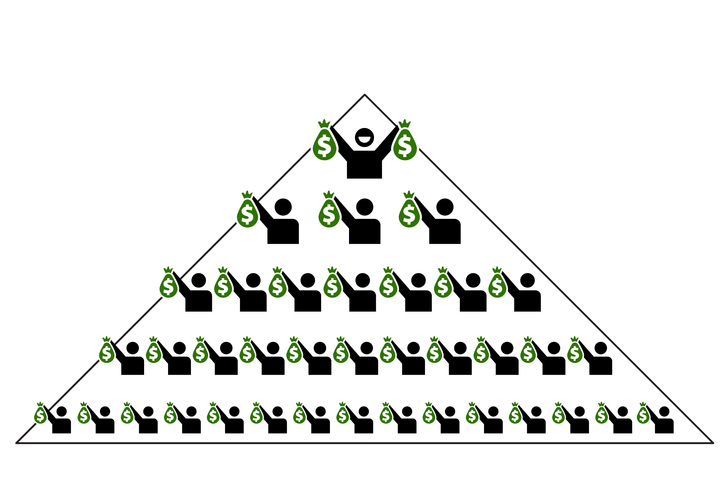

Most SNAP benefits go to the poorest households:

86% of benefits go to households with gross monthly income at or below the poverty level

51% of benefits go to those with gross monthly income at or below 50% of the poverty level

27% of households have gross monthly income above the poverty level, but receive only 14% of total SNAP dollars.

“SNAP is not just about putting food on the table; it’s an economic stabilizer, it’s a poverty alleviation tool,” Plata-Nino says.

SNAP not only helps families alleviate the stress of food insecurity, but it has local and broad economic benefits, as well. Every new dollar in SNAP benefits has up to $1.80 in economic growth benefits, according to a 2019 USDA study.

“When SNAP is disrupted, it ripples through entire communities,” Plata-Nino says. “It’s not just the families who lose food — it’s the small grocers, the farmers, and the local economies that depend on those dollars.”

Who gets SNAP — and stands to lose it?

If you were to compose the most statistically typical SNAP recipient, it would be a white child from a low-income family living in a rural area.

SNAP doesn’t target specific groups, like child nutrition programs or Women, Infants and Children (WIC) benefits do. The program serves people of all races, ages and regions. That includes the elderly, people with disabilities and caregivers. What all SNAP beneficiaries have in common is their income — nearly all are living below the poverty line.

“People are working incredibly hard just to survive,” says Plata-Nino.

Here’s a breakdown of SNAP program participant demographics, according to USDA data:

The majority are white: By race, 35.4% of SNAP participants are white; 25.7% are African American; 15.6% are Hispanic; 3.9% are Asian; 1.3% are Native American; 1% reported multiple races, while 17% are of unknown race.

Most working-age recipients are working: Twenty-eight percent of households earned an average $1,548 per month from work. “SNAP helps fill the gap between what people earn and what it actually costs to live,” Plata-Nino says. “It’s what allows parents to keep food in the fridge while still paying rent.”

Children comprise the largest age share: About one in three (39%) of SNAP participants are children.

Rural areas have the highest participation rates. Rural areas tend to have higher rates of poverty and food insecurity compared with other areas, according to an analysis by the Food Research & Action Center. Most total recipients live in cities — because most people live in cities — but proportionately, SNAP recipients are most likely to live in a rural area.

One in five are older adults. About 20% of SNAP participants are considered “elderly.” What’s fundamentally different about older adults receiving SNAP, as opposed to younger people, is that SNAP is a fundamental component of their already-fixed income, says Jessica Johnston, senior director of the Center for Economic Well-being at the National Council on Aging.

“For older adults, their circumstances are far less likely to change and so receiving a SNAP benefit, even in an amount as small as $50 to $100 per month is still proportionally a large part of their monthly fixed income,” Johnston says. She adds that it’s not a realistic expectation for most older adults to work more to fill a gap.

One in 10 are nonelderly with a disability. Roughly 10% of SNAP participants have a disability and are not elderly.

The overwhelming majority are U.S. citizens: 89% of SNAP participants are U.S.-born citizens, 6.2% are naturalized citizens; while 1.1% are refugees and 3.3% are noncitizens.

“This program is being utilized by Americans,” Plata-Nino says. “It’s children, older adults, and people with disabilities — the people who need it most.”

Food banks still face challenges

Even before the government shutdown, there are 50 million people who turn to the charitable food system to bridge the gap in their food budgets, says Ami McReynolds, chief advocacy & community partnerships officer, and interim chief government relations officer at Feeding America, a nonprofit network of 200 food banks.

Food banks have seen a sharp increase in demand since the pandemic, as more families face food insecurity. In 2025, SNAP and funding programs for other food assistance have taken hit after hit. Earlier this year, the Trump administration cut over $1 billion in funding to programs that supply food to both food banks and schools, part of an overall attempt to rein in the cost of social programs.

Then, following the passage of the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act in July, new work requirements have made SNAP harder to access, forcing more people to turn to food banks. Since the shutdown began on Oct. 1, food bank demand has also increased in areas with high populations of federal workers who may never have had to turn to food banks before.

“We often talk about that for every single meal that the Feeding American Network provides, SNAP provides nine,” McReynolds says. “We won’t be able to fill that gap, but we will continue to do our best to support our neighbors.”

Emergency food is exactly that — to be used in an emergency to fill gaps, says Jerome Nathaniel, director of policy and government relations at City Harvest, a large food rescue organization that distributes food for free across New York City.

“We are intended to support families whose SNAP benefits may not last the full month, which happens often, or families that may not be eligible, but we are certainly not designed or expected to fill the scale and scope that SNAP provides,” Nathaniel says.

What you can do to help

Ultimately, the safety and security of SNAP recipients is in the hands of lawmakers. When the shutdown ends benefits will be restored. Both Nathaniel and McReynolds say advocating is crucial.

“Making sure that you’re contacting your member of Congress and telling them the impacts of these cuts, what you’re seeing in your community, how this is affecting your family — that’s really the most powerful thing,” Nathaniel says.

“Food assistance is not a bargaining chip,” McReynolds says. “We’re asking everyone to reach out to their members of Congress. We need the government shutdown to come to an end and we need to make sure that folks who rely on WIC and rely on SNAP are able to see those programs funded because they are a lifeline for so many individuals.”

In the meantime, if you’re able, you can donate money, food and time to local food banks. Find your local food bank through the Feeding America network, Hunger Free America or by dialing or texting 211 through the United Way. There may also be little pantries, community fridges, mobile food banks and other local food distribution programs available in your area.

(Photo by Brandon Bell/Getty Images News via Getty Images)